The countdown is on for The British Shooting Show – book tickets online today and save on gate price!

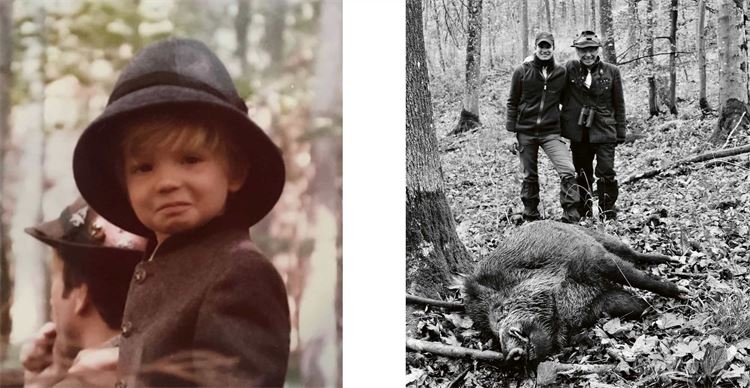

The wild boar masterclass with Franz-Albrecht zu Oettingen-Spielberg

An exclusive, first of its kind interview with one of the modern era’s most celebrated hunters.

Franz-Albrecht zu Oettingen-Spielberg is something of a legend in the driven boar hunting world, thanks to his incredible reactions, skill at spotting and identifying animals, and marksmanship that produces clean kills time and time again. In this exclusive interview we look at the similarities and differences between driven bird shooting and driven boar shooting, and Franz not only talks about how he started shooting, but also gives his advice on technique and shares 10 top tips.

Can you remember the first boar you ever shot?

I can – I started shooting as soon as I could, and from an early age my father took me to shooting ranges for shotgun and rifle. I soon developed an interest for moving targets with a rifle. I was getting to know and understand the species for the first few years. I shot my first boar on a driven hunt when I was on a stand with both parents, and with no warning my father handed me his rifle.

Who taught you?

My father taught me, starting before I ever picked up a gun. An accomplished Shot himself, he nearly made the Olympic trap team in 1972. During this period he also held a number of German and European titles. I spent a lot of time with him in the stand, watching and learning. I remember the first time I saw him shoot driven wild boar. I must have been about six and I was annoyed that I hadn’t been allowed to join the hunt in the morning because I had school. But in the afternoon, I joined both my parents on the stand. My father got a right-and-left with my grandfather’s 8×57 double Holland & Holland. What was amazing was that after that, for many years, I never saw him miss, and he killed things cleanly every time I was watching. He didn’t pretend that he didn’t miss, or that things didn’t go wrong sometimes, it’s just that I never witnessed it.

When I started shooting, with a .22, my father set out targets at a long distance and asked me if I thought I could hit them. I remember saying I would try. He stopped me and said: “Franz, we don’t try. You either know you can hit it or you don’t take the shot.” He was very strict about that – I was taught never to take chances when shooting at live quarry. The probability of a clean kill should be extremely high, otherwise you don’t take the shot. I want to know that I can kill something cleanly, not just hit it.

What has changed since you started shooting wild boar?

I’d say in the last 25 years, with the expansion of wild boar numbers across Europe, the need for agricultural control has increased in line with this, exposing more hunters to this form of population control than ever before. A whole industry has been created around it, but it’s not just that. It’s the way the days are organised, the equipment, the training people do before going shooting, the tracking dogs, how the game is treated after it has been shot. People are taking it much more seriously and spending much more time training – be they hunters or dog handlers. It’s very similar in the world of driven bird shooting, where Guns spend more time at a shooting range practising on clays. For driven boar we now have shooting cinemas, which has changed the way we can train.

Where would be your favourite place to shoot wild boar?

I’ve been fortunate enough to hunt wild boar in quite a few different countries, but each one has something special about it. One of the things that stands out are the people I’ve met and the different traditions they have introduced me to in their culture. Whether it is Hungary, Spain, Czech, France, Austria, Germany – they all have something special and they are passionate about boar. In every destination I have hunted, I have learnt something, and been able to bring that back and apply it to our own strategies, to the benefit of our driven days at home. Of course, being able to host a hunt at home is very special. It can also be stressful. You are worrying about safety, being a good host and ensuring the right animals are taken to achieve the yearly quota set by the state, in order to balance the wild population with its habitat.

What is your most memorable experience?

That’s a tough question. Every hunt teaches you something new, and I enjoy adapting my shooting and developing new techniques. One of the most important things is keeping up ethical standards – I’m sure every shooter, whether it is for larger game species or feathered game, feels the same satisfaction when they shoot something cleanly.

What is the hardest shot at driven boar and why?

You can cater for anything in terms of speed and distance as long as you understand your lead distances and bullet speeds. Ideally, the boar is on flat ground, in a not too wooded area, at around 40 to 50 metres, running broadside. Anything else starts getting more complicated. It gets tricky when you aren’t hunting on flat ground – if it is hilly, or the boar has to change speed, for example. You have to adopt different strategies for different situations, so it is largely down to experience. It’s not something you can train for. You can certainly improve your technique in a shooting cinema, but there isn’t the same level of instruction available as in clay shooting.

What’s the most common mistake you see being made out in the field?

One of the most common mistakes I see is flinching. Flinches come and go – I get them too, more than you’d expect. When you are training, you need to have the right proportion of dry-fire training and actual shooting. It’s important not to over shoot when you are training – that can do just as much damage as not training at all.

Other commonly made mistakes are those relating to fieldcraft: not knowing when to sit down or stand up in any given situation; not knowing when to take the first shot at a group of boar or which boar to start with; not being able to identify the correct sizes and sexes of boar quickly enough, in order to seize every opportunity. These will all have a big impact on your success.

How does the art of driven boar shooting transfer to driven bird shooting or vice-versa?

There’s a lot that is very similar. The tactic of pulling through or sustained lead is the main thing that transfers between the two, but with boar you have the added complication of following through. You’ll almost always be shooting in forestry, which makes following through a challenge as you don’t want to hit trees. I use a combination of pulling through and sustained lead, and sometimes I hold over on the far side of a tree if I know that’s where the boar will appear, then flick through as I see the boar’s nose. You need to have a good variety of strategies, just as you do to be a good gamebird Shot – no two animals are ever going to be the same.

Tools and technique

We asked Franz-Albrecht what advice he’d give on tools and technique. Here’s what he said:

Choosing the right calibre is fairly important. I use a .270, but when I first started shooting wild boar, I was told to “take enough gun” and I started with a .30-06. I then moved on to a .300 Win Mag and then a 9.3×62, thinking the more gun I had, the more successful I’d be. It took me a while to realise that lower recoil and a faster bullet were much more important than a heavy-load cartridge. With the .270, I find it is more flexible, more accurate and quicker to handle. For most shooters, however, a .30-06 or a .308 is a good option – they are universally popular calibres, which means you can find pretty much any speed and weight of cartridge for them.

In Germany, in fact in most of Europe, I’d say that 90–95 per cent of the boar we shoot are well under 100kg, so there’s no need for a very heavy bullet. With training and accuracy, a well-placed .270 bullet will do the job on any larger animals. The reduced recoil makes a huge difference and allows much better bullet placement and therefore less meat damage, and gives you a much quicker follow-up shot if required. Anyone who says they don’t have a problem with recoil probably hasn’t experienced the difference. If you try shooting a heavy load from a .270 and then a heavy load from a 9.3×62, you’ll see what I mean. It’s true that when you are shooting live quarry you aren’t always aware of recoil, but your body and your subconscious is, and it can lead to flinching, and the recoil can mean you lose sight of the boar.

To further reduce recoil, I also use a muzzle break which takes another 30–50 per cent or so off the flip and jump of the barrel, and makes it more comfortable to shoot. The downside is that the report is much louder, so good ear protection is vital. You can use a moderator but it does change the balance and weight of the rifle, and you don’t want it to be too heavy – having said that, a certain weight at the end of a barrel can actually help the smoothness of your swing.

Another thing to consider is a rifle’s trigger – it should be clean and crisp, yet require no muscle power to squeeze.

A good weight is between 500g and 750g, I find, so make sure you can adjust the trigger and that you know exactly where it breaks. And, of course, you need a rifle with sufficient magazine capacity, as well as a good speed of repeating.

I’d say more important than all of those factors is that you use a rifle you are comfortable with and know well. Gunfit is something that is all too often ignored and can drastically affect your shooting. The stock fit is often forgotten – the length is important so that you aren’t stretching for the trigger, but also the comb height – you shouldn’t have to adjust your head for your sight picture to be correct.

When it comes to sights, you can use anything from red dot to open sights or magnified scopes. It really does depend on the situation. Field of view is important – you want to see obstacles coming, to be able to adjust or keep on your line. A rangefinder is also part of my equipment – it allows me to measure the distance to certain features from the stand and then adapt my lead in relation to the distance.

In terms of technique, there are a lot of similarities to shotgun shooting, as we discussed. However, one of the main differences is that you use your hips more with a rifle. The less tension you have in your upper body, and the less you are gripping the rifle, the smoother your movement will be. To achieve that, I find the best policy is to have a fairly rigid upper body and arms, with both elbows sticking out at an almost 90-degree angle from your body to give you stability. If you shoot from the right shoulder, right foot placement is vital (vice-versa for a left-handed Shot), and then let your hips do the work.

In driven boar shooting, just like in bird shooting, you can miss behind, in front, above or below. We want to keep as close to the horizontal line as possible while swinging, as that reduces the chances of missing above or below. If you try to use your arms, you’ll have a lot of vertical movement. So, the smoother and lighter your grip on the rifle, and the less upper body strength you use, the better. You can never eliminate vertical movement altogether, but you can reduce it and make it a rounder movement.

In terms of where you want to hit the boar to give a clean kill, you can either use the line of the eye of the boar, or you can go a touch lower on the centre of the boar – I usually stick to the eye-line. The anatomy of the boar is a strange one – the spine drops very low below the ear. Anyone going to shoot boar should definitely study their anatomy.

Safety

With all forms of shooting, obviously safety should be your first priority in every situation. Don’t only think of it during a drive, and never let it become routine. Keep reminding yourself of it, as during a driven shoot, whether for birds or boar, there are so many distractions. The last safety briefing of the season is as important as the first.

Rules

Every shoot day has its own rules on what you are allowed to shoot. You’re there to enjoy yourself, but you are also there to do a job, especially when shooting game where there is a quota set by the state that needs to be met by the end of the day. Don’t get confused by what you are and aren’t allowed to shoot.

Ethics

With all shooting of live game, ethics should be one of the main considerations. If you are unsure of making a clean kill, don’t take the shot.

Identification

Knowing the species and how to identify and sex the animals is vital. The quicker you can do that, the more time you are left with for shooting.

State of mind, state of body

Make sure you get a good night’s sleep before a shoot. Have a good breakfast, but don’t drink too much coffee. I don’t drink coffee before a shoot – I react strongly to it, and find I get shaky if I do. Focus on what the hazards are and don’t lose concentration.

Know your equipment

Everything to do with handling your equipment needs to be a reflex; from changing the magazine to changing the magnification on your scope. Think of it like driving a car – your focus should be on the road rather than looking at your gear stick.

Know your distances

You should know the velocity of your cartridge and use a rangefinder to measure distances so you can calculate lead. You need to understand the rough guidelines for the speed and distance of the boar and the lead you need to give it.

Clothing

If you are too cold or too warm, you’ll shoot badly. You don’t want to sweat when you are walking between drives, either, and you need to have a good range of movement. Layering will have a huge impact on your comfort and you’ll shoot better as a result.

Training

Do lots of repetition, lots of dry-firing, lots of shooting (but not too much so that you develop a flinch!), and train on the range. The more you do, the more you’ll understand your equipment, your weaknesses and strengths, and the more instinctive your shooting will become.

Decisions

You’ll have to make split second decisions – which is why all the above are so important – so that you can focus on your shooting and make the right call. Every chance that you get is thanks to your host’s preparation for the day. It’s your responsibility to be ethical and do the job well. Make the most of it.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.