- News

- Game shooting

- Fly fishing

- Big game

- Sporting art

- Guest editors

- Gear

- Competitions

- More

-

-

More

-

- No posts selected.

-

-

-

-

★ Win a Schöffel Country shooting coat for everyone in your syndicate worth up to £6,000! Enter here ★

History of red grouse shooting

Fieldsports Journal takes a detailed look back at what is widely considered to be the king of gamebirds.

Often referred to as the ‘King of gamebirds’, the red grouse is unique to the British Isles and has a shooting season which runs from 12 August – the ‘Glorious Twelfth’ – until 10 December. The bird is now confined to the north midland counties, northern England, parts of central and north Wales, parts of Ireland and Scotland. Prior to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, red grouse were present throughout Wales, Scotland (other than the Shetland Islands) and Ireland. Abortive attempts were made to introduce the red grouse into Norfolk and Suffolk as well as into parts of Sweden and Germany during the late 19th century, while successful introductions were made on Dartmoor and on Exmoor during the early 20th century, allowing shooting to take place on a limited scale in the latter region until the early 1970s.

Historically, the red grouse was considered by ornithologists to consist of two sub-species: the British red grouse (Lagopus scoticus scoticus) and the Irish red grouse (Lagopus scoticus hibernicus), which usually has a very slightly paler winter plumage. The former sub-species were said to be found throughout England, Wales and mainland Scotland, while the latter sub-species was apparently confined to Ireland and the Outer Hebrides. This supposition has now been discounted by scientific experts who regard both sub-species to be one and the same bird, Lagopus lagopus scoticus.

The red grouse has been managed for sporting purposes since the early 19th century. Management, however, is carried out through habitat enhancement, vermin eradication and poaching prevention rather than through artificial rearing (although it is possible to rear the birds in captivity). In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when labour was plentiful, it was common practice for gamekeepers to provide grit and water supplies on a grouse moor as well as to feed the birds in severe weather by placing stooks of corn at various points on the moor. Red grouse stocks at this time were improved by introducing Scottish birds onto moors in Yorkshire and Lancashire and vice versa in order to introduce new blood in a locality. Further, in north Wales and in Yorkshire, a number of small moors were operated specifically for grouse production, whereby mature birds were netted on a regular basis and supplied to landowners whose stocks had become depleted due to overshooting. In the late Edwardian period, red grouse could be bought from Yorkshire dealers for 30/- (£1.50) per brace, a brace in this instance consisting of two hens and a cock!

For example, in 1913, Major Duncan Matheson purchased a total of 50 brace of red grouse from Mr F. S. Graham of Aysgarth in Yorkshire for the sum of £75 in an attempt to improve the native grouse stocks on the 6,000-acre grouse moor on the Aline deer forest on the Isle of Lewis, which yielded between 100 and 200 birds in a good season. In order to monitor how many of the imported birds were brought down either at Aline or on adjoining shoots, the Major had the entire consignment fitted with a ring bearing an ‘A’ prior to release!

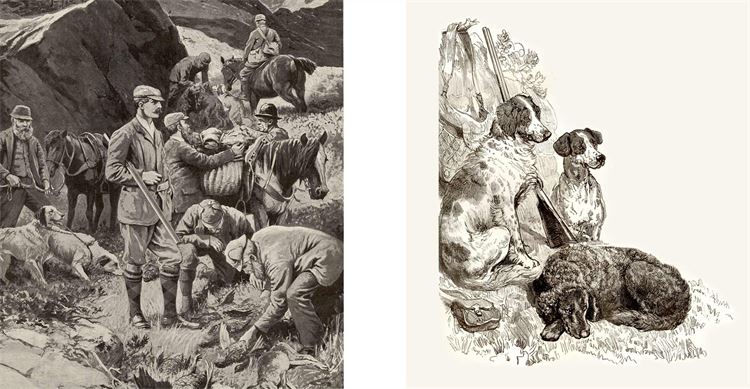

Considered by many to be the ‘rich man’s’ gamebird, the red grouse has been walked-up and shot over dogs since Stuart times. Grouse shooting, however, did not really become fashionable amongst the aristocracy and the landed gentry until the early years of the 19th century when some of the more intrepid sportsmen of the day began to undertake shooting expeditions to the English, Welsh and Scottish moors, travelling to their destination by carriage or on horseback over the new turnpike roads and staying at inns or farmhouses for the duration.

Going walked-up grouse shooting at this time was not for the faint-hearted, as Henry Alken points out in National Sports of Great Britain, published in 1821: “Grouse lie best in fine weather, and may, in the early season, be followed from eight o’clock in the morning, as long as daylight lasts, provided the stamina and inclination of the gunner last also. A good refreshment at midday will forward this. Late in the autumn, from ten-to-two or three o’clock, is the longest shooting day. Large shot and the heaviest gun a man can conveniently carry will be found most effective, as the birds will run to a great distance. Sportsmen generally try to kill the old cock, which runs cackling away, in order to deceive and lead the pursuers from the brood. The cock being dead, the pack will lie until the dogs run upon them.”

Sportsmen experimented with grouse driving during the early years of the 19th century as a means of securing larger bags – grouse driving of some description, apparently, took place on the Bishop of Durham’s moor at Horsley as early as 1803 – but the practice did not come into general use until the Victorian period. Landowners subsequently began to construct lines of purpose-built butts – originally known as ‘batteries’ – made of stone or wood surmounted with freshly cut heather turfs at various points on their moors to accommodate Guns and their loaders when shooting.

Contemporary estate records indicate that driven grouse shooting had started to take place on the Duke of Rutland’s moors at Longshaw in Derbyshire in 1849, and was being carried out on a regular basis on the Duke of Devonshire’s moors at Bolton Abbey in Yorkshire by the late 1850s. Driving grouse had become commonplace on many of the moors in Yorkshire and Co. Durham by the 1870s and was introduced on the Lowther Estate in Westmorland by the Earl of Lonsdale in 1876. By the 1890s, driven grouse shooting had become the principal mode of killing grouse on all of the larger moors in England, Wales and Scotland and on many of the smaller moors, too.

Red grouse shooting on a large scale really began from the 1870s onwards, with ever-increasing annual bags culminating in a record for the period when eight Guns brought down 9,929 birds on the Earl of Sefton’s Abbeystead estate in Lancashire on 12 August 1915. The development of grouse shooting as a sport was helped immensely by the extension of the railway system to the north of England and Scotland, thus making it possible to travel from London and the south of England to the north in hours instead of days. Indeed, by the early years of the 20th century, fast railway connections between seaports such as Southampton, Liverpool, Tilbury and the moors enabled American millionaires, Indian princes and maharajas to visit Great Britain by transatlantic liner or the weekly Indian mail service from Bombay in order to shoot grouse, some of whom came on an annual basis.

Unlike pheasant and partridge shooting, both of which tended to be the preserve of the shoot owner and his invited guests rather than paying clients until the 1970s, grouse shooting was commercialised during the mid 19th century with many English, Welsh, Scottish and Irish landowners letting out their moors to wealthy businessmen or members of the aristocracy and the landed gentry either annually or for a month or a fortnight at a time. It was something of a tradition on some northern moors for the owner to let the shooting from 12th August until the end of September or early October at a relatively high rental and to retain the remainder of the season for his own use. Accommodation for paying Guns was either provided in a specially built shooting lodge (often referred to as a ‘shooting box’) or in a local inn or farmhouse dependent upon the size of the moor.

The demand for red grouse shooting from British and overseas paying Guns remains buoyant at the present time and the sport not only generates a significant income which benefits many rural communities, but also makes an immense contribution to wildlife habitat management in moorland areas. Grouse shooting is now generally sold by the day rather than for a week or a month at a time. It has become more accessible to the less well-off sportsman, many of whom are able to afford the occasional walked-up day towards the end of the season. Moorland proprietors, of course, continue to invest heavily in their grouse moors, employing gamekeepers and estate workers to manage the land in the best interests of grouse preservation and nature conservation, whether or not they run a commercial or private shooting operation.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.