Game shooting

Ptarmigan territory

Sport on the high tops, where the terrain is as unforgiving as the quarry is unpredictable

Would you like to appear on our site? We offer sponsored articles and advertising to put you in front of our readers. Find out more.

Wild and remote places do something to us. They capture our imaginations even before the mention of any type of hunting. Perhaps it’s the escapism they offer; perhaps it’s the sense of perspective they provide…

The fact is, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to find such places, particularly on our small and crowded island. So when Mark Osborne of William Powell Sporting kindly extended an invitation to shoot ptarmigan at Phoines estate in the Scottish Highlands last season, I jumped at the chance. Regardless of the sport on offer, I was confident the 800-mile round trip from Lincolnshire to this 25,000-acre sporting Mecca in the west of the Cairngorms National Park would be worth it.

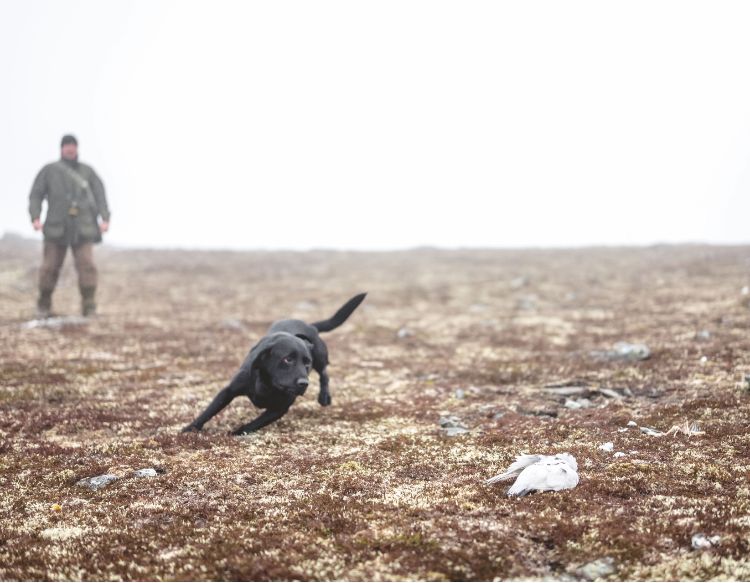

The day’s shooting started as so many of the best do – a team of like-minded sportsmen packed into an ATV with slipped guns and keen dogs. On this ‘ride out’, however, we’d have to hold on tight; the vehicle pointed steeply uphill, destined for the milky-aired abyss of the high tops. Ptarmigan territory.

The environment is as unpredictable as the bird itself; after completing the final leg of the ascent on foot, the fog en-cloaked our party as it formed a line. Each breath was visible in the early December air. Our hands slowed down in the cold.

It was quiet up there, so far away from the hustle and bustle of civilisation. Just the crunch and scuff of boots on the lichen-laced scree and rank tufts of old penny-coloured heather. Then, every now and again, the windy silence would be punctuated by the unfamiliar creaking call of Lagopus mutus, the master of camouflage.

The ptarmigan jumped and another, previously unseen, joined the escape effort, both flying at chest height and away from us. Shots rang out and as one of the pair fell to the ground, the second bird, quite surprisingly, arced round and headed straight back towards us. I’d never seen anything quite like it.

The British Trust for Ornithology estimate there to be 8,500 pairs of rock ptarmigan in Britain, and it quickly became apparent why shooting activity has little effect on these numbers. Milder weather patterns and untidy tourists – the rubbish left behind by the latter attracting unnatural numbers of nest-raiding corvids – are thought to be significant factors, but to shoot ptarmigan is an infrequent affair. We were, in fact, the first people to pursue the bird in this part of the Monadhliath mountain range for a few years.

Indeed, what the quarry lacks in hazard perception is more than made up for by the physical challenges posed by the environment it calls home. Rocks that have laid still for centuries shift and slide underfoot; fields of slippery granite boulders intersperse the route; gulleys and ravines do their best to break the line as soupy mist swallows those within it. And then a ptarmigan jumps and in the few seconds between flush and ‘too far’, one must find their footing, ensure the shot is safe, mount and shoot. All this with numbed fingers and half an eye on the positioning of dogs and fellow Guns, who, not surprisingly, were happy to keep on the move in the inclement weather.

Might it be the most unforgiving gamebird shooting to be enjoyed on our shores? I suppose foreshore wildfowling falls into a similar category. Ptarmigan shooting parties are generally small, numbering 2 to 5 Guns, and the shooting itself is usually put on hold until late October when the stag season has drawn to a close and those estates with a healthy grouse shooting schedule – just like Phoines – have had the last of their driven days.

The ptarmigan is very similar in structure to its better-known cousin of the lower ground, but slightly smaller in size. They moult thrice yearly – their body plumage turns a brown colour with fine black and white barring around April time, progressing to grey in the autumn, before gradually switching to a pristine white in October in preparation for winter. Males retain their red comb throughout the year.

We flushed three more of the beguiling little birds later that morning; several of our party did not spend a cartridge.

But as we stopped to sate hunger and thirst, and the fog lifted to unveil the Monadhliath mountains about us, it didn’t matter, for we were in ptarmigan territory, far from the madding crowd.

A thank-you must go to William Powell Sporting who arranged and hosted the experience. For further information on sporting opportunities at the Phoines Estate, contact wills@jmosborne.co.uk

www.williampowellsporting.co.uk

www.phoinesestates.co.uk

Related articles

Game shooting

The Glorious Nineteenth

Rhode Island may not immediately come to mind as a prime destination for a shooting trip, but The Preserve Sporting Club and Resort is changing that perception.

By Time Well Spent

Game shooting

Lunar escape

Likened by some to shooting on the moon, Morocco’s El Koudia is full of adventure, unique experiences and an abundance of terrain that you simply won’t find elsewhere

By Time Well Spent

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design. By subscribing, you’ll gain access to authoritative content from plain-speaking writers who tackle complex subjects with confidence and experience.

Plus, UK subscribers enjoy exclusive benefits including £2 million Public Liability Insurance for recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles and airguns. Whether you’re a seasoned shooter or an intrigued novice, a Fieldsports Journal subscription is your gateway to enhancing your field sports endeavors and staying connected to the country way of life.

Manage Consent

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Functional Always active

The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network.

Preferences

The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user.

Statistics

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you.

Marketing

The technical storage or access is required to create user profiles to send advertising, or to track the user on a website or across several websites for similar marketing purposes.