The Indian shikar

Sporting activities in the days of the British Raj.

The tradition of ‘shikar’ or organised big game hunting in India dates back to the 18th century, when army officers and civil servants employed by the Honourable East India Company (HEIC) began to hunt tigers, bears, antelope, elephants and a variety of other exotic species during their leisure time, usually as the guests of Indian maharajas and princes. Over the years, the term shikar began to embrace a number other sporting activities introduced to India by the British Raj or ruling class, including gamebird shooting, angling, pig sticking and fox or jackal hunting carried out by foxhounds imported from England.

Following the formation of the Indian Empire in 1857, the British Government, who took over the administration of India and the various Indian armed services from the HEIC, began to set up vast game preserves in many parts of the sub-continent, often in states under the control of native rulers. These preserves, sometimes divided up into a number of dedicated shooting beats and equipped with luxurious lodges and bungalows, were then set aside for the use of native rulers and their guests, military personnel, and visiting dignitaries from Great Britain and other parts of the empire.

Aware of the need to conserve Indian game species for the benefit of sportsmen, the British administration gradually introduced legislation controlling shooting seasons and bag restrictions in certain areas, culminating in the Indian Game Protection Act of 1912. In addition, virtually every state had its own subsidiary regulations requiring sportsmen to purchase shooting licences, protecting sacred birds such as the peacock, and operating vermin bounty systems whereby any person who killed wild dogs, wolves, leopards and other predatory creatures could claim a cash payment upon production of the skins to the secretary of the local Game Preservation Department.

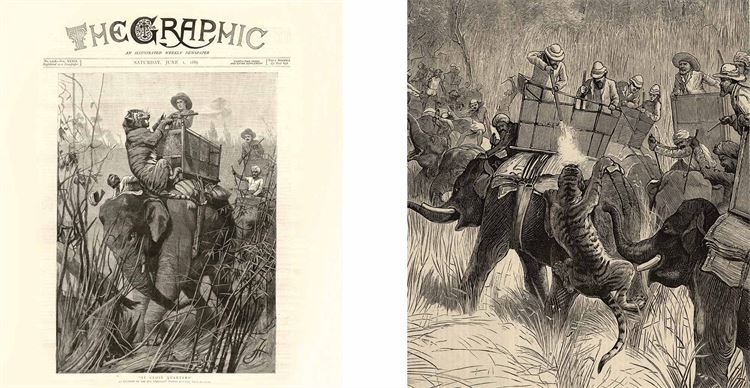

Shooting expeditions in the days of the British Raj were often ostentatious affairs involving hundreds of native attendants and beaters who accompanied groups of VIP sportsmen deep into the jungle in pursuit of tigers, bears or rhinoceros. Large encampments were set up where Guns could sleep in luxurious mosquito-proof tents and dine in style on tinned provisions and wines imported from Fortnum & Mason in London. Guns often travelled from beat to beat upon horseback during these events and shot at their quarry from ‘howdahs’ mounted on the back of elephants!

For example, when King George V visited Nepal for a 10-day big game shooting expedition in the Chitawan Valley in December, 1911, as part of his Coronation Durbar tour of India, more than 14,000 men were involved, including suites of courtiers and diplomats, beaters and attendants, with around 600 elephants being employed for transport purposes. Two shooting camps were set up 50 miles apart, connected by specially cut roadways through jungle and forest, each with an electrically lit bungalow with dining facilities to accommodate the King and his entourage. Support services available at both camps included taxidermists, a field hospital, a laundry, post offices, stables, chauffeured motor cars, mechanics etc. The total bag taken on the expedition amounted to 39 tigers (21 being killed by King George), 18 rhinoceros and 4 bears!

The more impecunious sportsmen such as junior army officers or middle-class civil servants rarely took part in large-scale big game hunts unless extremely well connected. Instead, they shot snipe on the numerous areas of bog found in many parts of India, rode out with the Madras, the Ootacamund, the Peshawar Vale or one of the other British style hunts in pursuit of the fox or the jackal, or fished for Indian trout, mahseer or tengara, all of which could be caught in rivers and streams throughout the Indian sub-continent.

Some impressive bags of game were taken by sportsmen in India during the period of the British Raj. For example, the Viceroy of India, Lord Irwin, and a party of Guns shooting at Sariska in 1929 accounted for a bag of 10,000 imperial sand grouse; in 1938, the Maharaja of Jaipur and a number of guests brought down a total of 4,273 wildfowl on a specially created area of wetland at Keoladeo Ghana; while on an un-specified date during the late-Victorian period, Mr Lionel Inglis, a well known sportsman, shot a leopard in Kashmir measuring 9′ 1″, believed to be an all-time record length for a leopard.

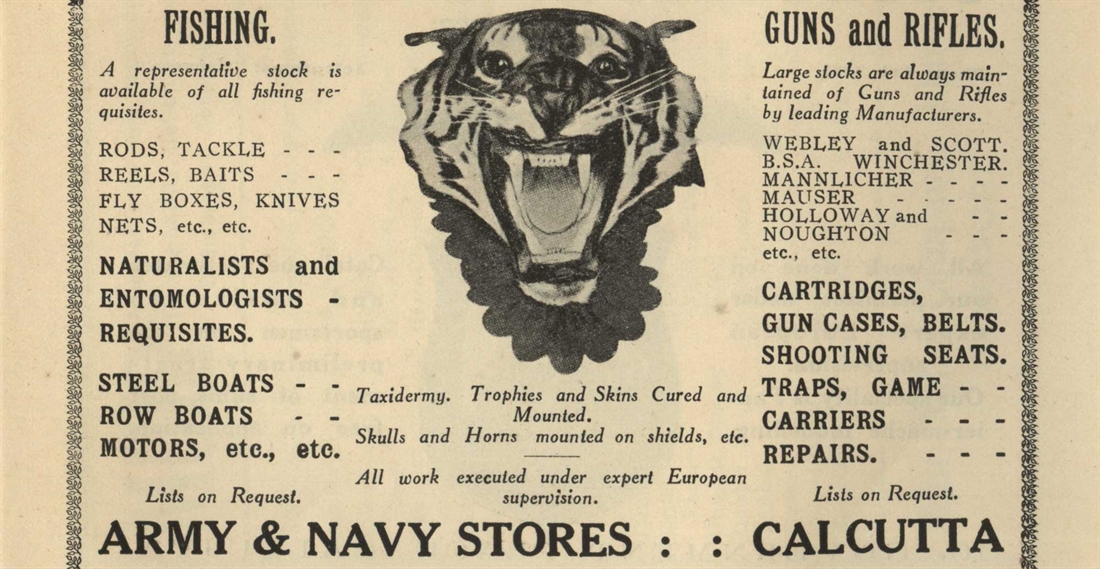

Inevitably, the enthusiasm for shikar in India during the 19th century led to the establishment of firms of specialist gunsmiths who manufactured or imported guns and rifles from Great Britain for ex-patriot sportsmen; tailors such as Hall & Anderson of Calcutta who produced khaki shooting outfits and topees which could be worn in extreme climatic conditions of heat or humidity; and camping equipment suppliers who provided mosquito-proof tents, portable washing equipment, folding card tables and other accessories necessary for comfortable sporting expeditions. A number of taxidermy businesses were set up in large towns, too, enabling members of the Raj to have their ‘trophies of the chase’ stuffed and mounted and, eventually, sent back to Britain to be displayed and admired in country houses or suburban villas.

Special shikar gamebooks were even produced for the sporting fraternity in India containing two sections: one for ‘small game’, the other for ‘big game’. The small game quarry list included columns for the bustard, peacock, jungle fowl, partridge, pheasant, woodcock, sand grouse, quail, various species of wildfowl and ground game, as well as salmon, trout, mahseer and other fish. The big game section list covered an equally eclectic variety of quarry species ranging from bison, tiger, panther and bear to ibex, chinkara, thar and goral, along with spotted deer, swamp deer and other types of deer.

Not surprisingly, a thriving sporting press flourished in India throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, producing the Indian Field and various other periodicals devoted to the pursuit of shikar. Numerous books were published on the subject also, as well as several annual handbooks, including the Hoghunters Annual, which ran from 1928 until 1939, and the Indian Field Shikar Book, an indispensable guide which gave in-depth information about every species of bird, beast or fish to be found on the sub-continent, and contained lists of game regulations for each state.

Shikar continued to be a popular pastime amongst members of the British armed forces and civil service based in India right up until the nation was granted independence in 1947. Thereafter, many species of big game suffered at the hands of farmers who wanted to protect their crops and poachers who were out to profit from the sale of animal by-products such as elephant tusks. Sadly, today, despite the intervention of the World Wildlife Fund and associated conservation organisations, numbers of tigers and various other animals formerly preserved and hunted by sportsmen are now perilously low.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.