Roe deer in Great Britain: A brief sporting history

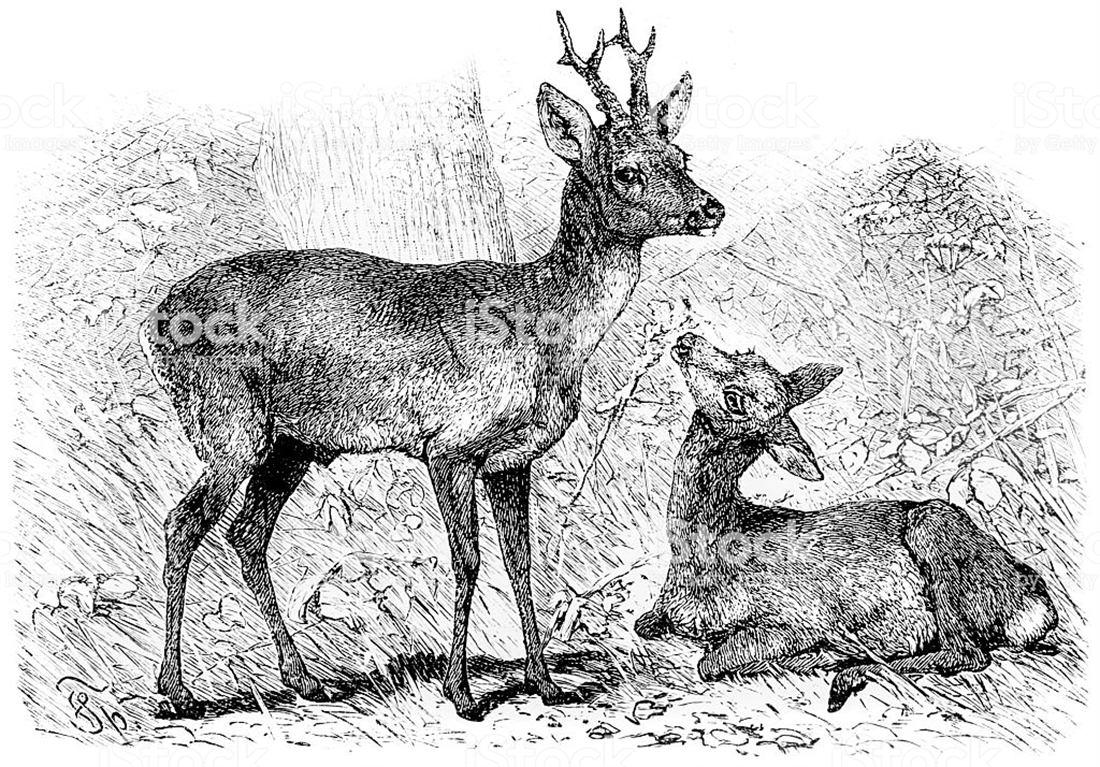

Attitudes towards what many consider the 'prince' of the UK's deer species have changed considerably over the years.

Over the past 50 years or so, roe deer stalking has dramatically increased in popularity with sportsmen and women, many of whom not only pursue roe for woodland management purposes and high-quality venison, but the opportunity to get close to a fascinating quarry. The species has not always enjoyed such status, however –attitudes towards what many now regard as the ‘prince’ of the UK’s deer species have changed considerably over the years.

One of the principal royal beasts of the forest during the Norman period, and on a par with the red deer, roe deer were commonly found throughout much of Great Britain until the late medieval era. Their populations gradually began to decline in many areas of England following a judgement made by the Court of the King’s Bench in 1388 which de-classified the roe as a ‘Beast of the Forest’ on the grounds that it ‘drove away other deer’. The roe deer was subsequently re-designated as a ‘Beast of the Warren’, thus losing the protection of the Forest Laws, which led to their extermination in the royal hunting preserves by crown foresters. This, combined with the continuous loss of woodland cover over the following 400 years, resulted in the species becoming extinct by the 18th century in virtually every English county apart from those in the far north and north-west of the country.

In contrast, the roe deer fared significantly better in many areas of Scotland, where they were traditionally preserved for hunting and coursing with hounds until the 18th century. Thereafter, the primary method of pursuit was to employ a team of beaters with dogs to drive roe out of woodland or plantations towards a group of Guns standing on open ground armed with shotguns rather than rifles. This meant that they could also kill any winged game that might be flushed. Small-scale roe stalking was tried out on a few Scottish estates during the mid-Victorian period but was generally frowned upon by the sportsmen of the day.

Sporting landowners re-introduced roe deer into parts of the south of England from Germany, Scotland and elsewhere for hunting purposes in the early 19th century, using hounds and harriers in Dorset, the New Forest and on the Berkshire-Surrey border. But this was discontinued following the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Roe coursing with greyhounds was also apparently undertaken on a regular basis in Dorset during the late Georgian and Victorian periods.

These introductions of roe for hunting purposes proved to be highly successful with the result that within 50 years or so, roe deer populations could be found from Dorset in the west to Sussex in the east and as far north as Wiltshire and Berkshire. Indeed, roe became something of a pest on country estates in the southern counties where they were either killed as vermin by gamekeepers to prevent crop, woodland or garden damage, or shot as an incidental by-quarry on organised driven shoots. Sadly, few historic bag records for roe deer survive as they were usually relegated to the ‘various’ column in gamebooks and seldom logged in vermin registers. Often, roe were the perk of the headkeeper or senior beatkeepers and as such the carcases were either sold to a game dealer or the venison distributed amongst family and friends.

In the far north of England, in the Lake District and other localities where indigenous roe populations had not become extinct, the deer were either shot as vermin by gamekeepers, sportsmen or farmers, or occasionally driven out of woodland by hounds towards a small team of Guns armed with rifles or shotguns standing on open ground. Using the latter method of shooting, which was most effective when carried out in early morning, it was often possible to take a bag of around half-a-dozen roe.

Roe deer continued to be regarded as a pest rather than a sporting quarry in England from the Victorian period until the outbreak of the First World War. Indeed, writing about roe and rabbits as nuisances in his book Shooting in 1902, Alexander Innes Shand states: “The roe is as destructive as it is ornamental, which is saying a great deal. It is an unmitigated scourge to both forester and farmer”. Not surprisingly, roe are generally only mentioned in passing, if at all, in 19th- and early 20th-century English shooting or gamekeeping literature.

Throughout the war years from 1914 to 1918, roe deer were destroyed for pest control purposes and shot or poached to alleviate food shortages. Thereafter, they continued to be targeted as vermin by landowners and by the newly-formed Forestry Commission who actively encouraged their destruction due to the damage they caused to woodland plantations.

Shooting enthusiasts, it appears, first began to stalk roe deer with rifles in England on a limited scale as an alternative form of sport from the 1920s. Apparently, ex-soldier sportsmen and gamekeepers started stalking on the Lulworth Ranges and other military sites in Wessex at the invitation of the War office, too, in order to keep the sites clear of roe deer. Some landowners also introduced the practice of shooting roe with rifles from strategically placed high seats in woodland at this time.

The species continued to be thought of as little more than vermin by the vast majority of sportsmen, landowners, gamekeepers and Forestry Commission officials until the 1950s and early ’60s, particularly in Forestry Commission forests and plantations and private woodlands. In fact, it was not until Richard Prior – then a Forestry Commission vermin trapper but now regarded by many as the ‘father of roe stalking’ – and a few colleagues began stalking roe in preference to indiscriminate shooting in the 1950s, that procedures started to be established for roe stalking which laid down the foundations of modern-day deer management.

Surprisingly, given that roe and other species of deer have been pursued for sporting purposes in Great Britain since time immemorial, apart from laws enacted during the medieval period, they had received minimal legal protection up to this time. Indeed the passage of the Deer (Scotland) Act of 1959, and the passage of the Deer Act of 1963 applicable to England and Wales – both of which established a close season and forbade night time shooting – broke new ground in deer management procedures. Similarly, legislation was passed which stated the minimum size of the calibre of rifle and the types of ammunition that can be used to shoot roe deer.

Stalking roe deer began to increase in popularity in the late 1960s, particularly amongst less well-off sportsmen who could neither afford to be involved in a driven shoot or stalk red deer in Scotland but were in a position to rent stalking rights for a moderate fee from a private landowner, the Forestry Commission or another public body which owned land. Roe stalking at this time could also be obtained through membership of the Saint Hubert Club and a few country hotels who offered ‘all round’ sporting facilities for guests.

Since the 1970s, roe deer populations have increased dramatically throughout Great Britain, not only moving north from their traditional southern strongholds but also south from the north of England and Scotland and outwards from Thetford Chase in Norfolk where they were introduced around 1884, making them the most widely distributed species of deer in the country. Management procedures have improved over the ensuing decades along with the implementation of training schemes for stalkers, both professional and amateur, by various accredited bodies. Alongside the increasing appetite for qualifications such as Deer Stalking Level 1 and Level 2 Certificates, game meat hygiene training and facilities have also improved considerably with the result that roe venison now finds a ready market amongst game dealers and other buyers.

Today, the roe deer is no longer seen as a pest providing a ‘poor man’s sport’, but as a respected game quarry species which needs to be managed to maintain a healthy but sustainable population in our varied countryside. Roe stalking has grown in status over the past 40 years or so becoming the southern equivalent of Scottish red deer stalking, and can either be carried out alone by a suitably experienced and qualified sportsman, or with the assistance of a knowledgeable local guide or stalker who takes an enthusiast out in pursuit of a suitable beast to harvest.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.