Hunting ibex in the swiss alps

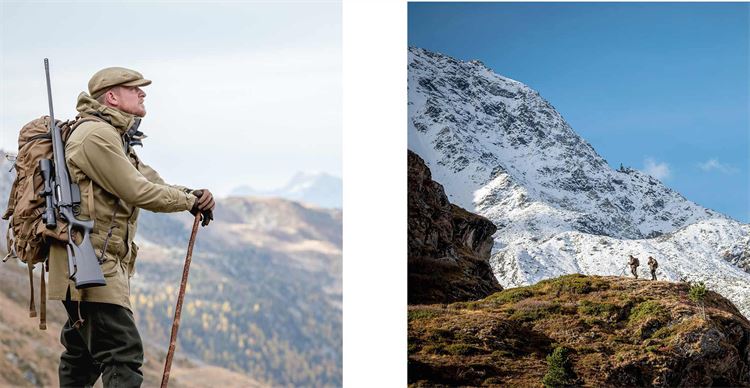

A hard-to-come-by hunt in the Swiss Alps creates memories that will last a lifetime.

Nearly a decade ago, I stayed in an Austrian castle, its walls adorned with architectural-looking alpine animal skulls. Perhaps the most intriguing of those was a goat-like creature, its crescent horns stretching far back, the ridges heavy and defined, like knuckles on a clenched fist. It was the most noble of all European game; a steinbock, often known as an alpine ibex. Its sheer magnificence sparked my imagination. This, surely, was the Marco Polo of Europe. That these wild and majestic creatures inhabit the high slopes of the Alps seemed extraordinary to me, and I knew then that this was one beast I wanted to hunt in my lifetime. Ever since that first experience, mountains and their goat and sheep inhabitants have crept right under my skin. Indeed, in the intervening years, I have been privileged to hunt a number of other goat and sheep species including the Mid-Asian ibex in Kyrgyzstan and the Beceite ibex in Spain, but my dream of hunting an alpine ibex persisted.

Finally, in a system unique to Switzerland, I drew a tag to shoot a mature male alpine ibex in the Valais Canton area of the Swiss Alps. A tag for one of these remarkable creatures is as rare as hen’s teeth and is literally a once-in-a-lifetime chance. Many foreign and local hunters alike enter the state-run lottery, most for over 10 years before being rewarded with their opportunity. Each year, some 200 ibex are hunted in the French-speaking region, just 30 of which are mature males (or what we used to call ‘trophies’ before Cecil the lion made headlines). Many of the mature males are shot by foreign hunters like myself paying a hefty pricetag for the opportunity. Here’s the tricky bit for the greenies: the income generated from these mature males funds the management of all wildlife in the Valais, as well as the rangers who perform this task.

Christian Bornet, my guide, has been the ranger in the Valais for 30 years, and it was clear from the outset that he knew not only every crag and crevice, but also all the locals – human and animal. Being born and bred here, he explained, is vital to his job: “Locals would not respect someone who wasn’t from the Valais. I know them, and they know me. They call me if an animal has been hit by a car, or there is a problem.” As to the animal population, Christian and his fellow rangers perform a census in the autumn and another count in the spring of all species found in the area, which decides their cull numbers for the year. There tends to be little variation as Christian explains: “If the winter has been very hard, it may have killed some animals, so we might shoot a few less.” Older animals are selected for culling, because, as Christian puts it, “It’s better to allow a 12- or 13-year-old bouquetin to be hunted, which will bring money into the community, than to allow it to die on the mountain of old age or starvation. Sometimes they get too cold and weak, and are eaten alive by foxes.” Bouquetin, if you hadn’t already guessed, is the French word for male ibex.

We spent our first night at altitude in Christian’s rustic cabin, warmed by a log burner, speculating what the next day would bring and talking about hunting in the Valais. Heading out at daybreak, we started our ascent on foot, soon leaving the rusty-coloured larches behind us as we passed the treeline. Christian was as nimble as the quarry we were pursuing. The conditions were tough – we were dealt fog, bad visibility and heavy rain as we climbed higher, aiming to get to the altitude at which we’d find our quarry. “We have to get above the weather system,” Christian said, as he kept up his unrelenting pace, “there is the mer de brouillard today.” The mer de brouillard, meaning sea of fog, rolled in and out of the mountains governed by miniscule changes in temperature, living up to its name.

Forced ever upwards by the weather, we passed an alpine lake, the Lac du Cleuson, and against my then form, luck was on my side and the sky cleared, revealing the snow line at higher altitude. With shards of sunlight now breaking through, we found ourselves in splendid isolation, the humdrum of the civilized world far below hidden in swirling fog and mist. “There, you see that peak?” Christian asked as we paused for breath. “That is the Bec des Étagnes, the highest mountain in the region. Étagnes is the female ibex.” At an altitude of 3,232m, the peak towered high above the mist, the snow white against the bright blue of the sky. The weather was certainly improving, as was my fortune.

We continued our climb, hitting the snow line, the altitude and frigid mountain winds now catching my breath. Underfoot, the snow was crusty and treacherously icy. It had melted then refrozen multiple times creating a polished surface with zero friction. I was incredibly grateful for the crampons I’d now fixed to my boots that gouged into this impossible surface. In a month, this area would be impassable for all except those on skis, Christian told me, and they’d be going downhill, a much easier prospect than the sheer slopes ahead of us. It was then that we spotted a group of mature males, eight in all. Christian sighed. “There is an easy side of this valley, and a hard side. We have to go along the hard side if we want to get to them.” He estimated it would be four or five hours before we could get within sensible shooting range of 200–300m.

We’d also need to climb upwards – in between our position and that of the ibex, there was an ice fall, crevices, and a boulder field to negotiate. Climbing higher and higher, we paused often to check on the group, and to rest not only our legs, but our minds, too – climbing these mountains requires absolute concentration. There were a few times that I lost my footing, setting my heart pounding. A fall here would be lethal, with no trees to stop you tumbling down to rocks below. “Slow motion when you move,” Christian advised. “That way you will not make a mistake.”

I took his words literally, putting each foot in front of the other with the stealth of a woodland stalker, and the going, though slow, was less perilous. As the hours passed, we made progress, taking advantage of dead ground where we could, and moving around the mountain face to keep downwind of the animals. Coming into the boulder field, we had to slow down even more, for there were crevices, and if the snowy slopes had been treacherous before, now every step could result in a limb-breaking fall. Soon, however, we hit a plateau, giving us a breather from the hard work of mountaineering. Stopping to look at the ibex, which were now 400m away – still too far for a shot – we planned our final approach.

There was some dead ground between us and the ibex which we could use to our advantage, and I’d have to make the shot at a steep upward angle if we were to avoid being seen or scented. Christian led the way, clearly considering each step he took to ensure we remained undetected. Finally, he stopped and signaled for me to set up for the shot.

A huge boulder made the perfect rest, not only stable but also hiding our silhouettes from the animals above us. I checked the distance with my Leica Geovids: we’d made it to 157m, and an angle of around 45º. Christian pointed out which beast I was to shoot – a huge mature male. He estimated his horns to be between 90 and 95cm in length which matched the licence I had drawn in the lottery based on the animal criteria.

This blue-blooded looking creature was scraping away the snow to feed on the tufts of grass beneath and slowly making its way towards us, stopping every few paces to scrape and nibble. We waited, the chill now seeping into layers I had removed then put back on after four hours of sweaty toil. And then the ibex turned broadside to me, lifting its head to look out over his domain. Putting the crosshairs low on its chest to compensate for the angle, I breathed shortly out and fired. The sound of the muzzle-break echoed around the mountain, completely disguising any sound of a bullet strike; I was relieved I had remembered to put my ear defenders on. The ibex ran forward a few paces before dropping dramatically, spraying snow into the air high above as it fell, then falling more than 100ft, and slithering down the ice.

“Perfect shot,” said Christian, clapping me on the shoulder. “But now the real work begins.” It was a further 30 minutes before we finally got to the animal. What a creature. His majestic horns, 97cm in length, bore the signs of age and the life he had enjoyed in his mountain kingdom, and as I touched the gnarled tips, a wave of gratitude for having been granted this privilege swept over me.

Christian calculated the animal’s age, counting not the knuckles but inner ridges of the horn marked with a distinctive annual indentation, and proclaiming him to be 12 years old. This larger than average beast weighed around 100kg. “The ibex are at their heaviest at this time of year, as they need to store as much energy as possible for the winter,” he explained. It would be impossible to carry the carcass back down the mountain – and far too dangerous to attempt to drag the beast. We caped it, for this was surely one for the taxidermist, and quartered the carcase, dividing the joints between us so that the meat could be delivered to a local restaurant, Le Mont Rouge.

That night, as we dined on well-hung backstraps of another mature ibex male expertly prepared by Loris Lathion, chef at Le Mont Rouge, I reflected on the day, on a hunt that I’d always dreamed of, that I’d imagined so many times. The danger with a dream that comes true is that the reality often doesn’t live up to it, or, once realised, a sense of deflation kicks in, in the knowledge that this was it.

This time, however, the reality more than surpassed the expectations formed when I’d first seen that ibex on the wall of the Austrian castle. And though I may never shoot another alpine ibex, the memory of this spectacular hunt, in these majestic surroundings, were enough to sustain me for a lifetime.

www.jagdreisen-international.de

The Alpine ibex

Believed to have been present in Switzerland for no less than 18,000 years, the alpine ibex (Capra ibex) came close to extinction in the early 19th century – primarily through intensive hunting. Just a few hundred survived in the Gran Paradiso National Park in Italy. Reintroductions from this small population started towards the end of the 19th century.

During and just after the Second World War, the ibex was once again in trouble, requiring more reintroductions and careful management. Today, the total population of alpine ibex is believed to number 47,000, with 15,000 in Switzerland.

It was for ibex that the first animal conservation project in Switzerland was formed, and the species, thanks in part to sustainable hunting, is now listed as ‘Of least concern’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Threats to the ibex today do not include hunting, though poaching is still a potential issue.

The problems lie with the narrow gene pool, hybridization with domestic goats and the reduction of alpine meadows, which are reverting to forest. One of the main threats is human disturbance, which is a threat to all mountain species – the worst of these being skiing, particularly of the off-piste variety. This disturbs the mountain ungulates during the winter when they are at their most vulnerable, forcing them to expend too much energy.

The alpine ibex’s preferred habitat is open rocky ground at high altitude above the treeline, and on steep, south-facing slopes. The ibex migrate to different altitudes according to the season, ranging far higher during the summer months, and heading downhill during the winter to find food.

The lifespan of an ibex is typically 10–14 years, and they occur in maternal herds. Males are solitary or live in bachelor groups, which disperse in October and November, with males joining the female herds during the rut, which is from November to January. Males are 90–100cm at the withers, with a weight of 65–120kg, and horns are 65–110cm in length.

Hunting in the Valais

There are 2,500 hunters in the Valais, and the hunting is strictly controlled, with each hunter having a quota. Swiss hunters must pass an exam which takes two years of training. The hunting season runs from September 15 – February 15 (each species has its own season).

As a foreigner, for the chance to hunt an ibex you need to know a Swiss National who can guide you through the tricky paperwork and lottery system, or work with an outfitter. I opted to go with a German outfitter who was extremely professional and worth the €500 fee to arrange the whole experience. But brace yourself, due to high demand and limited availability (not to mention Sterling plummeting post Brexit) prices start for a mature 85cm male at €8,500.

Kit bag

Sauer S404 Synchro XTC in .300 Win Mag

Leica Magnus 1.8×12-50

Hornady 180 gr SST Superformance

Leica Geovid HD-B 10×42 binoculars

Swazi Waipiti Coat

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.