Big game

An Interview with Professor Rory Putman

Fieldsports Magazine talks to deer biologist and Chairman of the British Deer Society, Rory Putman.

Would you like to appear on our site? We offer sponsored articles and advertising to put you in front of our readers. Find out more.

When/where/how did your interest in deer come about?

In a sense it is always difficult to know quite when one becomes aware of anything, or when fascination creeps up. When I was a child, my family lived in Oxfordshire and my mother would sometimes, as a treat, take me to visit the fallow deer in the deer park attached to Magdalen College, so I was certainly exposed at an early age! Although at that point we lived in town, my father was a countryman and so every weekend we would be out and about in the countryside; his enthusiasm and knowledge certainly instilled a love of wildlife in me.

I suppose my real fascination with deer themselves developed when I returned to Oxford to do my doctorate degree. I lived and worked in the University’s field site within Wytham Woods (indeed I barely left the woods for the better part of two years…). At that time the woods were unfenced and home to a small population of fallow deer – perhaps no more than 60 or 70 in total – and the fleeting glimpses I would catch through the trees captivated me.

What is it about wild deer that you find so captivating?

My love of nature has always been as much a visceral, emotional thing as intellectual! Because of where I live and because of my work, I come across wild deer almost every day and people always imagine that by now I would have become somewhat blasé through overfamiliarity. But the honest truth is that I still get a real buzz, a real quickening of the pulse when I encounter deer, and will always stop to watch and wonder. My first passion was for fallow deer – and I still find them so very elegant (I have a real weakness for the females in all the species!) with their delicate stepping gait and those ever-twitching tails. Roe play in the fields outside my house and they too are so very dainty. Living as I do in the Scottish Highlands, I suppose the species I most often encounter are red, and although one is supposed to think of them as ‘majestic’ and ‘iconic’, I find them also simply beautiful. As a biologist I also take great pleasure in how well-adapted all species are to our wild landscapes.

How long have you been involved in deer research and ecological studies?

I spent a good deal of my youth avoiding becoming a biologist. In part this was due to the fact that, in those days, zoological studies largely comprised dissecting one’s way through the animal kingdom – but I also had a deep-seated fear that studying biology as a formal academic discipline would somehow rob me of my naturalist’s sense of awe and wonder at the natural world and spoil for me my lifelong hobby. I needn’t have worried. Although I went to university to study mathematics, I soon ended up switching to zoology and discovered to my delight that rather than detracting from it, a deeper understanding of ecology, of evolution, and of animal behaviour, enhanced my enjoyment.

My first job was as research assistant to the great behaviourist Robert Hinde at Cambridge University’s sub department of Animal Behaviour, before I returned to study for my doctorate at the Animal Ecology Research Group in Oxford. After completing that I was fortunate enough to gain a position as a lecturer in the Biology Department of the University of Southampton, where as well as teaching undergraduates I established a major research group undertaking primary research in wildlife biology and wildlife management. In 1996 I was appointed Research Professor in Behavioural and Environmental Biology at the Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU).

Subsequently I left the university system to return to Scotland and enter practice as a wildlife consultant; however, I retained an association with MMU where I continue to hold an emeritus chair. I also have a visiting professorship at the University of Glasgow so that while much of my day-to-day work involves offering advice on management of deer and other wildlife species, I still continue to undertake research and publish regularly, so that I am both an ‘academic’ and a management practitioner; what is, I believe, known as a ‘pracademic’.

Both within the university system and thereafter, my work has been focused primarily on the behaviour and ecology of deer and other large herbivores, and the impacts of grazing on the environment. As a researcher, the main thrust of my work was in applied studies and in utilising improved understanding of behaviour and ecology to develop better-informed and more effective management systems for the animals and their vegetational environment; I now try to put the results of that improved understanding to use when offering practical help and management advice.

Do you stalk/have you stalked, yourself?

With a camera only. But I have been around shooting and shooters all my life. As a child many of our family outings with my father were to local woods managed for game shooting. As a teenager and through my early 20s I helped out at pheasant shoots in Oxfordshire and Hampshire. Throughout my research career (and particularly since my interests were in applied wildlife management) most of my field studies were carried out on working shoots – and since I started working for myself up here advising on deer management, my whole life has been spent amongst deer managers and those who shoot. And I eat a lot of venison.

But I have never felt the urge to shoot, myself – a curious anomaly in that much of the management advice I have to offer to clients is about a need for culling and population reduction. I don’t have good eyesight and I think perhaps a fear that I might mess up the shot and not kill the animal cleanly has always been a bit of a barrier.

What does your role at The British Deer Society entail?

I think I am probably the first non-stalker to take on the Chairmanship! Formally, I chair an elected Board of Trustee Directors who set the agenda for the society’s activities and help to move it forward. The actual day-to-day running of the society is handled by a dedicated staff operating from the same premises as the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust in Fordingbridge, led by our General Manager Sarah Stride. We have no formal CEO so I suspect in some ways, Sarah and I fulfil that role between us. I am extremely fortunate with the current board. While they are all deer enthusiasts, they offer between them a tremendous range of skills in IT, money management, business, governance, education and training so that it forms a really strong team to compensate for my many weaknesses! And I took over as Chairman at the point where they had just completed a review of the society’s position and activities and developed a strong strategic plan to move it forward over the next five years.

So I guess my role within the society now is to help to deliver that plan, to ensure that we better serve current and potential future members – whether they be stalkers and deer managers, biologists, photographers, artists, chefs or simply keen naturalists – and the society is truly to be the go-to place for objective and unbiased information and advice on deer and their humane management.

Are you involved in any particularly exciting research projects at present that you can tell us about?

I am hugely fortunate in being able to combine my work as an adviser with continuing research. In practical terms, however, I wouldn’t think much of myself as an adviser if, after having made suggestions perhaps for changes in management on one or another property, I simply left them to it and didn’t continue an interest – monitoring deer numbers and distributions, monitoring impacts on the vegetation, monitoring the productivity of the population etc. – to ensure that the management changes suggested were actually delivering their objectives! So by the nature of my advisory work I am continually collecting and collating information from that ongoing monitoring – which provides material for more academic analysis.

At present, with colleagues at the University of Glasgow we have just completed an analysis of the effects on bodyweight and reproductive performance of artificially reducing density in resource-restricted populations of red deer on open hill range in the Highlands. It is well established that as population densities increase, bodyweights decline, females take longer to reach puberty, mature females may breed only in alternate years, and calf survival declines. What has never been firmly established is what happens when you then reduce the density. Do these things reverse themselves in the same sequence (answer: no!) and is there perhaps a threshold density below which population numbers must be reduced before any response is observed at all? Another very interesting project in which I am involved is looking at impacts caused by deer on individual woodlands (ground flora and regeneration) and exploring over what scale culling needs to be coordinated for different species of deer before one can see a measurable change of impact in those same individual woods. The research always has an applied twist in the hope that we can continue to refine management practices.

What are the primary deer welfare issues currently at the fore in the UK?

Although the BDS is often ‘presented’ as a welfare charity, it isn’t as such. Our Articles of Association actually set out our objectives as: “The promotion in the public interest of research into the habits of and the scientific study of deer in the British Isles”; and “The promotion in the public interest of knowledge of methods of management, humane treatment and humane control of deer”. Thus our concern is primarily about humane treatment and humane management.

Clearly there are some pretty obvious requirements in terms of best practice when culling: that one ensures a killing shot; that one takes every precaution (even if it means not taking the shot) to ensure that killing of any adult female will not result in the orphaning of dependant young and so on. But in practice, good deer management also means being aware of the resources available to deer in their wider environment: do they have sufficient access to adequate forage resources? And, do they have sufficient access to topographical or woodland shelter?

I think one of the perpetual problems is that management is often considered at the site level and not the landscape level. One might, for example, consider the impacts of fencing a new woodland plantation on access to food and shelter for the local deer population – but how does that new fence act, in combination with other existing fences in the wider area, to alter deer distribution patterns and movements at the landscape level? This sort of perspective is often overlooked, yet poor forethought when fencing may often affect landscape-level movements – or even increase the risk of deer vehicle collisions by channelling deer down onto a roadway.

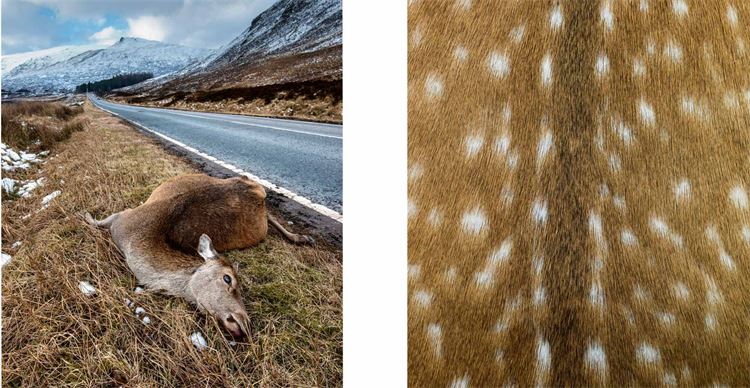

Such collisions between deer and vehicles remain of real concern. In the UK as a whole it is estimated that there may be more than 70,000 traffic accidents involving collisions with deer each year, with a conservative estimate of economic cost in excess of £15million. And while these figures refer to animals which are killed outright or humanely dispatched, many animals injured on our roads jump or crawl away to die lingering deaths out of sight.

Another issue of increasing concern is the effect of disturbance on deer. Public access to and enjoyment of the countryside is increasing dramatically – which is an excellent thing – but the resultant disturbance may have a negative impact on deer welfare, by disturbing natural patterns of activity (deer in areas of higher disturbance tend to become more nocturnal in habit) or in displacing them from favoured feeding grounds, as well as through direct effects of chronic stress. A ‘special case’ of this has been the increased harassment of deer – in the wild and particularly those within deer parks – by amateur photographers seeking ‘close-up’ photographs. There is clear evidence that this results in stress when females are having their young and may cause disruption of rutting behaviour, too. Let’s face it, the photographers themselves are taking an enormous risk: these are large and powerful wild animals and in self-defence can cause serious injury to humans! We have recently published on our website a code of practice advising photographers on the ‘dos and dont’s’ when photographing deer.

What, in your opinion, are the main challenges faced by deer managers in the UK?

At a practical level, collaboration! Effective management of the larger and more mobile, herding species of deer such as red, fallow and sika, requires coordination of activity over the entire geographic area in which a particular population may range. If efforts are not properly coordinated at that landscape level, they are not likely to be especially effective.

In the longer term, a changing demographic amongst those who stalk, with an increasing average age of stalkers – and changing public attitudes to ‘hunting’. This is a problem right across Europe and where a major part of the management of deer population numbers is delivered by recreational stalkers (or what are often referred to on the Continent as ‘hobby hunters’), this is potentially a really serious issue. An increase in the average age of hunters is reported widely throughout Europe (as one example, the average age of hunters in the Czech Republic is around 60). In Japan the situation is even more acute with the average age of registered hunters now well over 70!

The situation is made still more complex, in that cultural attitudes towards hunting are also changing in many countries, and quite rapidly, as the result of a declining interest in hunting and with increasing urbanisation. To the extent that public attitudes and public perceptions may influence what is deemed ‘acceptable’, it is clear that changing attitudes may well influence management approaches, management systems and management legislation in the future.

This is potentially a serious problem not simply for those who enjoy hunting as a recreational pursuit and would not wish to be pilloried for that enjoyment, but also in terms of actual management of game populations. As noted already: in almost all countries in Europe, management of wildlife populations is dependent to a great extent on the efforts of these recreational stalkers. If fewer young people are training as hunters so that overall numbers of hunters are declining and, simultaneously, average age is increasing, then in practice, management capacity is getting smaller and smaller. Yet we know that at the same time, deer populations are expanding rapidly in both numbers and distribution across most of Europe; the need for management is increasing and thus in many countries there is projected to be a growing mismatch before too long between management need and management capacity where control of deer populations depends on the efforts of recreational stalkers. We must do more to change perceptions of hunting and to attract new, younger recruits to the craft of deer management.

Is the illegal poaching of deer (specifically in England) with use of night vision/thermal equipment a growing issue?

I don’t know whether this is increasing or not. Certainly one sees reports across the media of major slaughter in localised areas – but I suspect this has always been an issue. I remember when I worked on one estate in the early 1970s, being warned by the Headkeeper that there were reports doing the rounds of a gang who used a red Peugeot to reconnoitre a given area and would then come in with Land Rovers and Range Rovers, raking the targeted deer herd with semi-automatic rifles, picking up what dropped and then making their escape. He warned me not, under any circumstances, to attempt to challenge them if I saw them. The Peugeot duly arrived, but because of the nature of our ground there was no follow up. Sadly the underkeeper on a neighbouring property did challenge the same gang and was shot in the legs.

Organised poaching will surely always come and go, whenever the price of venison makes it more or less economic to take the associated risks?

What are the most common mistakes, in management terms, made by recreational stalkers?

Where does one begin?! The vast majority of stalkers are extremely careful and extremely professional in their sport. Most recognise that there is a responsibility upon them for humane and effective management of the deer population which supports their shooting.

Adequate training is key. A recent article published by the GWCT and BDS looking at the factors which affect the probability of injuring a deer rather than achieving an outright kill, highlighted that kill rates were higher and injuries lower when stalkers ensure a comfortable firing position, use a gun rest, aim at the chest, use bullets heavier than 75gr, avoid taking a rushed shot, shoot a distant animal only if there is plenty of time, fire only when the target is stationary, avoid shooting at an obscured animal, take care when the ground is unfamiliar, and partake in shooting practice at least once a month.

In general it seems to me that haste is always an issue – and not just in terms of risks of wounding. When shooting, stalkers should always remember that they are also managers for the population and consider the consequences of their ‘selection’ of what to shoot in the light of its longer term effects on the overall sex and age structure of the population and the likely future impacts of that same population on their environment. Ill-considered shots, disrupting the social structure ofa group or acting to cause dispersal into new areas, can result in increasing rather than decreasing impacts.

How can training and education for recreational deer stalkers be improved?

As a non-shooter myself, any advice I could offer would be somewhat hypocritical!

I think that the courses overseen by the Deer Management Qualifications team and delivered through organisations such as BDS, BASC and the National Gamekeepers’ Organisation in England and Wales offer a good introduction. In many cases too, although it is not a formal requirement in the UK, younger stalkers will accompany more experienced deer men in their early outings and can learn through a form of informal apprenticeship. Within Defence Deer Management, as in a number of Continental European countries, such an ‘apprenticeship’ is in fact mandatory.

Is there much we can learn in the UK from deer management practices overseas?

So much depends on circumstances and tradition, as well as legislation, established practice and the main objectives of management – and all these vary enormously from country to country (as indeed do the species present and their impacts and thus the focus of management effort).

Wearing a half-academic hat I was fortunate enough to work with two European colleagues (Professor Marco Apollonio for the University of Sassari in Italy and Professor Reidar Andersen from the University of Trondheim in Norway) on a major review of the status of deer – and other ungulates such as wild boar – in 30 different European countries. We considered the impact of these species on agriculture, forestry and conservation habitats as well as reviewing management practices in each country and the extent to which management practices were effective in controlling populations and reducing damage – or by converse might actually be contributing to making things worse!

This project (which actually resulted in a series of three major books) was extremely informative, and to me personally, very illuminating [Why do we always imagine that other countries practices must be broadly the same as ours?!]. But while there are some things which seem to work in some circumstances, the main take-home message is that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’, no universal best approach to management fit for all circumstances. And even if there was… so much of management practice in any country, as I say, is rooted in history, in the traditions (and game laws) and culture of that particular country, that any given set of rules does not translate easily from one place to another. FS

For further details on the British Deer Society, please visit www.bds.org.uk

Related articles

Big game

SAKO & TIKKA: PASSION FOR PRECISION

UNLEASH YOUR PRECISION CAPABILITIES DOWN TO 0.5 MOA ACCURACY.

By Time Well Spent

Big game

The MacNab

The Macnab Challenge – a salmon, a stag and brace of grouse in one day – has its roots in a novel by John Buchan. Simon K Barr finally succeeds after 10 years of trying

By Time Well Spent

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design. By subscribing, you’ll gain access to authoritative content from plain-speaking writers who tackle complex subjects with confidence and experience.

Plus, UK subscribers enjoy exclusive benefits including £2 million Public Liability Insurance for recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles and airguns. Whether you’re a seasoned shooter or an intrigued novice, a Fieldsports Journal subscription is your gateway to enhancing your field sports endeavors and staying connected to the country way of life.

Manage Consent

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Functional Always active

The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network.

Preferences

The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user.

Statistics

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you.

Marketing

The technical storage or access is required to create user profiles to send advertising, or to track the user on a website or across several websites for similar marketing purposes.