★ Win a Schöffel Country shooting coat for everyone in your syndicate worth up to £6,000! Enter here ★

Salmon fishing in Norway – the golden age

David S. D. Jones recalls the rise of the Norwegian fishing industry.

British anglers first began to visit Norway in the 1830s, lured by an abundant supply of salmon and sea trout and cheap rental fees. Indeed, many paid nominal sums of money annually to small farmers – each of whom owned the section of a river which passed through his land – in return for the sole fishing rights and board and lodging in the farmhouse, but on the condition that all fish caught were given to the riparian owner.

Salmon fishing in Norway quickly grew in popularity. Astute anglers acquired the fishing rights on long leases from adjoining farmers and small landowners in order to create sizeable fisheries on extensive stretches of river. Some also rented gamebird shooting and elk hunting rights in order to form sporting estates, built commodious wooden fishing lodges and employed local people as ghillies and domestic servants.

The Norwegian angling tourism industry had become well established by the mid-Victorian period, with many of the best rivers entirely in the hands of British sportsmen who were known locally as the ‘salmon lords’. Fishing literature was already available in the form of Forest scenes in Norway and Sweden: being extracts from the journal of a fisherman, written by the Reverend Henry Newland, Rector of Westbourne, an early angling visitor to Norway. The book was published in 1854. Travel information and assistance with transport to angling destinations, including advice on hospitality arrangements, could be obtained from Thomas Bennett of Christiana (Oslo), an Englishman who had set up a travel agency in the city in 1850 and produced Bennett’s Handbook for tourists in Norway which included lists of useful phrases for anglers and others. Last but not least, suitable fishing equipment could be purchased from J. McGowan of 7 Bruton Street, London, a tacklemaker established in 1857 who specialised in supplying the needs of the Norwegian angler.

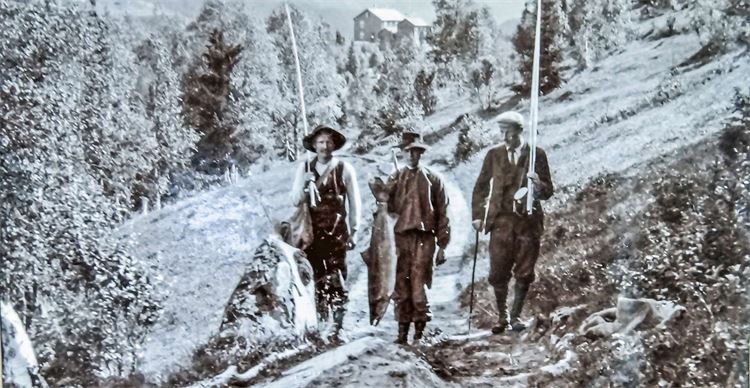

Fishing in Norway enjoyed a golden age from the late 1880s until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, attracting large numbers of British anglers annually, either on a seasonal, a monthly or a fortnightly basis. Many ‘all round’ sportsmen also combined angling with shooting, going out in pursuit of ptarmigan, black grouse, capercaillie, woodcock, hares and other game during the autumn months. They often hunted elk or red deer, too.

Specialist letting agents controlled the angling on virtually all of the Norwegian salmon rivers at this time. The two principal agencies being the Anglo-Norwegian Fishermen’s Association, who sub-let the fishing on waters held by British long-term lessees, and Messrs Lumley & Dowell of London, who not only represented a number of Norwegian agents who let fishing on behalf of various clients, but also produced an annual brochure of fisheries and river beats available, and a directory of associated lodge or hotel accommodation.

Norway was easily accessible to anglers by steamer, with regular services operating from Hull and Newcastle to ports such as Christiana (Oslo), Bergen, Stavanger and Trondheim, all of which offered road, rail or sea connections to the final angling destination. An overland rail-sea-rail route operated between London and Christiana, too, with luxury sleeping carriages for part of the journey. This was complemented by the special trains which Norwegian State Railways put on at the start of each sporting season to convey anglers and their equipment from many of the principal seaports and towns to the main fishing destinations, often operating in conjunction with scheduled bus or carriage services.

Salmon fishing in Norway seems to have been particularly popular amongst businessmen and members of the legal profession, many of whom did not have the time or the money to rent a Scottish sporting estate with its associated river and loch fishings, grouse moor and deer forest for the season, nor a prolific beat on a prestigious river. The Norwegian fisheries also attracted ‘destination anglers’ of independent means who usually arrived from late May onwards after fishing on rivers in the north of England or Scotland.

Sir Francis Denys, Bt., for example, a retired diplomat and a ‘destination angler and Shot’ who spent virtually all of his time angling, shooting or deer stalking, made his first visit to Norway in July 1893, staying in a farmhouse at Vold as the guest of Mr Nugent and Lady Agnes Daniell, who held the tenancy on about two miles of the celebrated Namsen river. He records in his fishing diary that he spent from 9am to noon and from 5:30pm until 11:30pm out on the river each day, generally being most successful after 7:30pm. His total catch, taken solely by harling from a boat during the course of 18 days on the water, amounted to 11 salmon (the heaviest weighing 27lb) and 4 sea trout.

In 1900, Sir Francis made a second visit to Norway together with his friend the Honourable Algar Orde-Powlett in order to fish for salmon on the Sundal river. He records in his fishing diary that they embarked from Hull aboard the Wilson Line steamer ‘S.S. Salmo’ at 5pm on 5 July, and arrived at Christiansand at 8:30pm on 7 July, paying the sum of £7 (£550 in today’s money) for a return ticket. They then made an onward journey by mail steamer to Sundal Soren before travelling to their final destination at Musgjorde where they had rented the four-mile Musgjorde beat for three weeks. Between them, they landed a total of 21 salmon, the heaviest weighing 22lb. Flies used include the Blue Doctor, Silver Doctor, Jock Scott, Durham Ranger, and Thunder and Lightening.

Four years later in 1904, Sir Francis returned to Norway once again, this time to fish on the Vefsna river near the town of Mosjöen. On this occasion he rented a beat at Fallan together with the associated fishing lodge for the month of August for an unspecified sum of money from Mr Richard Venables-Kyrke of Nant-y-Ffrith, Flintshire, a leading figure in Anglo-Norwegian angling circles. In addition to his wife, Lady Grace Denys, a keen fisher herself, his party consisted of his friends Colonel William Mitford and Major George Capel-Cure. Fishing began on 4 August and ended on 20 August, as the river had dropped too low to fish. Nevertherless, Sir Francis managed to land a total of 25 salmon, the heaviest weighing 31lb, with other fish of 28lb, 27lb and 25lb. Lady Denys caught five fish; Colonel Mitford, 12, including a 28-pounder; and Major Capel-Cure, 20, including a fish weighing 29lb. He notes in his fishing diary that prior to his arrival, his landlord, Mr Venables-Kyrke had caught a total of 93 salmon weighing an aggregate of 1,183lbs on the Vefsna!

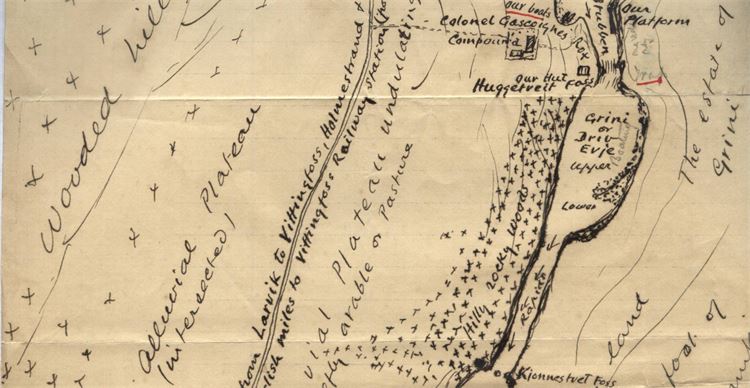

Obviously keen on Norwegian angling, Sir Francis made another trip to the country in 1908, paying a monthly rental of £400 (£31,500 in today’s money) for four beats belonging to a Colonel Gascoigne at Grini on the Laagen river some 25 miles from the port of Larvik. He arrived on 24 June and left on 24 July, during which time he caught 9 salmon weighing an aggregate of 112½lb, 5 grilse and 1 sea trout. His fishing companions, Colonel Hamlet Wade-Dalton and Major William Stobart, landed 12 salmon, 2 grilse and 5 sea trout, and 14 salmon, 4 grilse and 1 sea trout respectively during the same period. The most successful flies, apparently, were the Jock Scott, the Silver Grey and the Silver Doctor. Grini was said to offer some of the best fishing on the Laagen at the time, June and July being the best months, but the party were hampered by unsettled weather and often only went out on the river in the evenings.

Sir Francis Denys undertook his final Norwegian angling expedition in June 1913, fishing for salmon on the Förde river and staying at Sivertsens Hotel, Sondfjord. He paid a total of £134 (£8,000 in today’s money) for 25 days’ fishing, ghillie services and full-board accommodation. His total catch amounted to 16 salmon weighing an aggregate of 245lb, which included two fish of 26lb and one of 25lb.

Sporting tourism in Norway came to an abrupt end in the wake of the declaration of the First World War in August, 1914. British anglers were no longer able to visit the country due to wartime travel restrictions, while many fisheries were ‘mothballed’ for the duration. Large-scale salmon netting operations for food procurement purposes subsequently took place, severely depleting the stocks. Further, excess numbers of fixed traps were installed in the great majority of the rivers, the riparian owners selling the catch to fish merchants in order to maximise their income.

British anglers started to travel to Norway once again following the cessation of hostilities in 1918 but rapidly discovered that the salmon stocks had not only been decimated through over fishing but that the fish were generally much smaller than in the past. That said, many of the more enthusiastic Rods resumed their annual fishing expedition, paying considerably reduced rentals in return for less prolific catches than in the halcyon days of the pre-war era!

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.