Fly fishing

Golden char fishing in Japan

An exploratory trip to Japan’s Lake Akan in search of golden char.

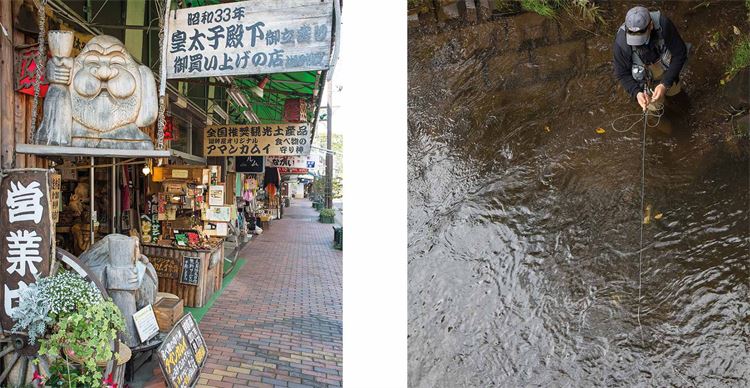

Some places fill you with awe. They leave one stunned, speechless at the sight of vast scenery, sinuous waterways and craggy mountainsides. At first glance, Hokkaido doesn’t boast such grandeur. Sweeping, tree-laden hillsides are too homey to conjure astonishment; the crystal-clear water lapping at the lakeshore invokes more relaxation than stark inspiration. The village of Akanko, nestled on the shores of Lake Akan, is more comfortable and serene than exotic. Schoolchildren zipping by on their bicycles give me a curious smile on my early morning walks through the village, and neighbouring shopkeepers offer the same as they open their humble businesses each dawn.

Perhaps it’s that very familiarity that is striking; I’ve travelled halfway around the globe to explore the fishery surrounding Lake Akan, some part of me expecting inundation in a dizzying new culture. And despite the readily obvious language barrier – few people speak any English and I, no Japanese – the area exudes a comfortable, almost eerily familiar feeling.

And then, a day later, we wander into a fairytale river in a dense wood and – oh, yeah – there’s that feeling. Wonderment. I watch robust, energetic rainbow trout hold against the current, readily rising to large caddis flies, easy to spot in the river’s crystal clear water, and wonder how it’s possible for a place such as this to even exist today.

No fish hatcheries exist in the region, an unusual circumstance which has led to an exceptional fishery. Fly fishing is still an ‘underground’ sport here; a small yet dedicated angling community can be found on the banks of Lake Akan and neighbouring rivers, but for the majority of the rural local population the very concept remains somewhat of a mystery. It’s good news for area fly anglers, who often have waterways to themselves with the common exception of one of the region’s bountiful brown bear population.

Located on the western side of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island, Lake Akan was formed from the eruption of two volcanoes, Mount Meakan and Mount Oakan. With a circumference of 26km, the lake is home to a variety of fish species, including rainbow trout, taimen, kokanee salmon and – perhaps most significantly – ‘golden’ char. The region boasts a stunning population of white-spotted char which take on a peculiar golden tone unique to Lake Akan. One local angler proudly explains the fish to me in a flurry of Japanese featuring two subtly profound words in English: “Champagne gold.” The iridescent, warm tint of the fish is a far cry from white-spotted char found in other corners of the world, including neighbouring Kamchatka.

Lake Akan supports a healthy population of the char, all of them seemingly tinted the elusive golden colour. Two-handed rods are in abundance, well-suited to reach out into the depths of the lake while seeking the char, and streamers and even nymph rigs are in vogue. The more innovative anglers, among them my host Dameon Takada, experiment with floating minnow flies, designed to look as if one of the lake’s many resident parr had a singularly rough day, tempting a char to eat on the surface. The flies are intricately tied, with eyes, a touch of red thread near the eye of the hook, and a silicone coating to imitate the ‘gumminess’ of the real thing.

I find Dameon’s suggested flies to be effective, but feel that experimentation is in the job description when exploring a new fishery. In that spirit, I tie on a large Orange Stimulator one morning during a pounding deluge, tempted by the sparse rises I’d observed before the rain hit. Less than five casts later, my hunch pays off: a healthy golden char takes the fly with an aggressive strike, diving deep to perform what seems to be the char’s ritualistic behaviour when hooked: act like a log. The fish makes one good run before growing heavy and bullish on the end of my line, but before long he’s at hand and having his picture taken.

A day later I find myself pushing through a dense undergrowth of ferns and vines in search of the river. Dameon’s bear bells chime before me with each step, offering a fair warning to any resident bears that we’re passing through. We split up on the river, each casting to more than our fair share of large rainbows moving in the clear water. I grin; this is sight fishing at its finest: chasing big, wild fish which, more often than not, reward an accurate cast with an eat.

Simply put, the rainbow trout of the Akan River are not shy. “They love big fly. This area, these fish,” Dameon shares. And he’s right. I ply various caddis imitations, never smaller than a size 12, over the fish. Food is in no shortage in the river, requiring casts to be directly in the feeding lane – accuracy is the name of the game. Tippet diameter is not of much concern (3X is recommended) but length is a factor (12ft seems to be the most effective) and good presentation is important. Casts are not long but a clean drift wins the day, and the first time I hook into one of these wild rainbows, I’m oddly reminded of South Pacific bonefish – these fish run. And in a brush-laden creek (not helped by the typhoon that had passed through days earlier), anglers must know how to manage fish. But those who do will be rewarded with dynamic fishing in scenery befitting a fantasy novel.

Hokkaido is Japan’s far north; the region sees a true four seasons, including a harsh winter, and part of the bargain for such an impressive fishery is that the season is short. The fishing season on Lake Akan runs from May 1 to the end of November, and the Akan River faces a similar season of May 1 to October 31. Winter brings a variety of diversions including ice fishing, but for fly anglers spring, summer and early autumn are the time to be on the water.

While fishing is productive throughout the season, local anglers particularly look forward to spring. According to local resort chef and zealous angler Masaaki Nofuji, the middle of June through July 10 is the best fishing of the year, offering significant mayfly hatches. The first hatch is composed of larger insects, while the second is smaller and orange-tinted. Small midge hatches occur from mid-May to mid-June, and terrestrial fishing on the rivers can be productive in the summer. June is the busiest month for travelling anglers, but Takada shares that few visiting anglers make the journey; most tourists are from Japan, with some from Korea and Taiwan as well. It’s rare to see a Westerner on the water (in a week spent in the area, I saw a total of two Western tourists).

Most travellers make their way to Lake Akan for one of three things: round marimo moss balls, the storied indigenous Ainu culture, or the lake’s famed hot springs. The lake is the only place in the world where algae grows into ‘marimo’ – perfectly round moss balls created thanks to the lake’s shape, bottom and water conditions, and particular varieties of algae in the water. The marimo balls are a significant tourism draw for the region, as is the heritage of the Ainu, the region’s indigenous people. Ainu culture survives remarkably and is thoroughly honored in the hot springs district. Visitors can take in a variety of Ainu ceremonies (my autumn visit was during the fire ceremonies) and watch traditional Ainu dances in the largest Ainu kotan (village) in Hokkaido. Streetside vendors offer traditionally-carved wooden creations in the Ainu style.

Japan is located on the Pacific’s famed ‘Ring of Fire’, and while this heritage results in a large number of earthquakes and seismic disturbances, it has the added benefit of producing a large number of natural mineral hot springs. Several of the hotels in Akanko have harnessed these hot springs into a variety of public baths. The steaming water offers the perfect respite after a long day on the water and many visitors will utilise the all-nude hot springs as their daily bath, soaking in a variety of waters and sweat rooms before putting on the requisite ‘house clothes’ and seeking out a local dinner.

At the Akan Yuku no Sato Tsuruga hotel, the open-air rooftop hot springs are the ideal place for a period of note-gathering recollection post-fishing. I soak in the roiling water, watching clouds skid across the sky before bumping against looming Mount Meakan, a quiet volcano resting just across the lake. Down on the glassy surface of the water, the lake’s ferry cruises to a casual stop at the village pier, unloading a motley collection of visitors and commuting locals. The ritual of the hot springs quickly becomes a routine part of my day; I’ve visited lodges around the world with hot tubs or banyas, but there’s something about the oddly communal experience that just seems to fit with the relaxed world of Lake Akan.

We’re a mere 1,126km from North Korea. Only 47km northwest lies Russia. Hokkaido’s proximity to potential aggressors is a stark contrast to the island’s placid provincialism, a fact I’m readily reminded of as we drive past military convoys on our journey through the countryside. Somehow the camouflage and armed vehicles don’t mesh with the dairies and cornfields, and are a startling reminder of the world outside of this mellow world of fishing and relaxation. When I ask, Dameon shrugs and notes that yes, it’s on his mind and no, he’s not going to let it interrupt his fishing.

Some truths are quite simple. One I learned long ago, is that fishermen, regardless of the language they speak or if they ply their trade in fresh or saltwater, are truly the same around the world. One rainy morning, I find myself in the backseat of a Toyota, Nofuji and Takada talking quietly in Japanese in the front as we trail a military convoy through the countryside. We stop at a countryside pit toilet for a break and, after a stroll around, I look back to see both men peering over the edge of a bridge down the road, looking into the river below. I laugh, realising it’s a familiar sight I’ve now seen on several continents. Regardless of language, regardless of location, fishermen will always look to the water.

Related articles

Fly fishing

On a spey quest

Avid fly angler and photographer Rasmus Ovesen embarks on his first ever trip to Greenland and loses his bubbling spey heart to the Kangia river

By Time Well Spent

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.

Manage Consent

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Functional Always active

The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network.

Preferences

The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user.

Statistics

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you.

Marketing

The technical storage or access is required to create user profiles to send advertising, or to track the user on a website or across several websites for similar marketing purposes.