Fishing for arapaima

Heading deep into the wilderness of the South American rainforest in pursuit of monstrous arapaima – one of the most astonishing things you will ever do with a fly rod in your hand.

As the big Airbus A320 lumbered up into the warm evening air above Manaus, I took one last long look at the serpentine curves of the Amazon River, receding into the last flickering embers of the day, far to the west. I studied the deep groove burnt into the flesh of my thumb, and thought yet again about my brief but unforgettable encounter with the leviathan that I had travelled 8,000 miles to tangle with.

The Solimoes River is, in effect, the upper Amazon River. It tumbles down out of the Peruvian Andes and then meanders its sedate course through the remote jungle, before its turbid, mud-stained waters blend with the relatively clear waters of the Rio Negro to form the mighty Amazon ‘proper’, just upstream of Manaus.

It’s almost impossible to imagine what those first intrepid conquistadors made of the Solimoes watershed. The region is, even to this day, a truly wild place, deep in the very heart of the rainforest. A dark wonderland populated by a kaleidoscope of stunning birds, butterflies, and giant otters. A lush emerald waterscape where jaguars prowl the forest, absurd pink dolphins roll lazily in the endless network of channels, and huge caiman lurk malevolently in the lagoons and backwaters. In addition, where the Solimoes meets another major Amazon artery, the Japura River, the bewildering network of channels and oxbows play home to another singularly remarkable creature unique to the South American rainforests… arapaima gigas: the red fish – the legendary ‘pirarucu’.

‘Gigas’ means giant, and arapaima are just that. They are about as big as freshwater fish can get. These colossal fish can grow to up to 15 feet in length.

Fifteen feet! Imagine that! To see these beasts pitching their vast forms through the glossy surface of an Amazonian lagoon is a simply breath-taking sight. Gliding through the dawn mists, it’s easy to conjure a vivid image of Francisco Orellana and his valiant conquistadors trembling in their dug-out canoes, with these unearthly beasts rolling all around, on a steamy morning much like this, fully 500 years ago.

Tragically, in the intervening centuries, these fish have been heavily impacted by savage overfishing, exacerbated by their habit of betraying their whereabouts by surfacing regularly to gulp air. While commercial arapaima fishing has been banned in Brazil since 2001, illegal fishing and habitat destruction are both continuing apace, and populations are still declining sharply.

If you want to see an arapaima, head to the fish market in Manaus. The place is full of them – freakish great carcasses that dwarf the other fish that are piled high in the endless stalls. Arapaima are, sadly, delicious to eat, and they fetch a high price. Although they are supposedly all farmed fish, rumours are that wild fish are still caught and sold, often with little regard for long-term sustainability.

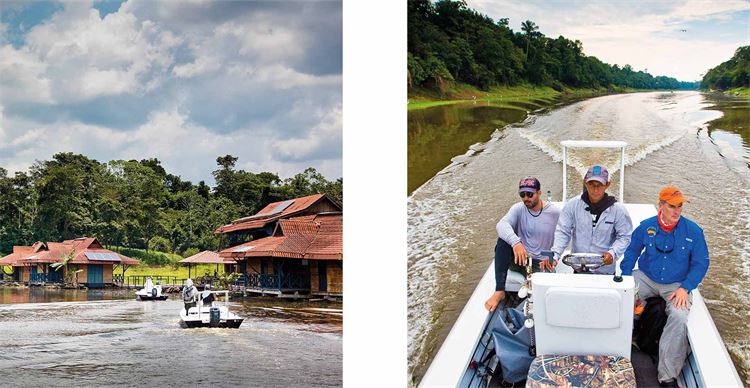

Fortunately, the Brazilian Government have set up a number of arapaima reserves. Mamirauá – based in the wetlands between the Solimoes and the Japura – is one such reserve, and it boasts a staggering biomass of these huge fish. After protracted negotiations, pioneering jungle anglers Rodrigo Salles and Marcelo Perez of Untamed Angling have managed to establish a sustainable fly fishing programme that allows strictly limited catch and release fishing for these monstrous fish, while helping to fund the policing of this special place. Rodrigo and Marcelo have named their operation simply ‘Pirarucu’, and having experienced the fishing, I can tell you that hooking one of these behemoths is one of the most astonishing things you will ever do with a fly rod in your hand.

There are a mind-boggling number of arapaima at Mamiruau, and when the fish are really ‘on’, the fishing is simply remarkable – three anglers caught no fewer than 66 of these fish in six incredible days in September 2017, with fish ranging to way over 200lbs in weight being caught. However, the fish can also be infuriatingly fickle, as they were when I visited for four short days in late October.

I am lucky enough to have travelled far and wide with my fly rod, and I like to think that I can usually get the job done. However, the arapaima of Mamirauá had me baffled. With vast shoals of sardine-like baitfish crowding the lagoons, persuading them to eat an artificial fly seemed almost impossibly tough.

Arapaima fishing is typically – though not always – a slow business, with long hours between action, and I was desperate to figure out a way to catch the fish more regularly. I have fished with all three of the guides at Mamirauá – Rafael Costa, Alain Pereira and Guilherme Manzione. They are all brilliant guides, and I have enjoyed sensational fishing with all three of them at Untamed Angling’s world-class trophy peacock operation at Rio Marie, in another remote corner of the Amazon jungle. They are still figuring out this young fishery, but they are way ahead of me in working these fish out. They counselled to fish flies tied by Allan – black and white flashy profile patterns with lots of lateral scale flash to imitate the sardine-like fish. How I wish that I had taken their advice!

While my good friend Lance Ranger did as he was told and fished exactly as prescribed by his guide, I was – in hindsight, rather arrogantly – determined to crack the code and push the boundaries of this still fledgling fishery. Thus, while Lance fished with the guides’ flies, using the 400-grain line they advised, and retrieving at a snail’s pace, I just had to experiment.

Every morning, as we headed out into the dawn, the endless forests resolving out of the mists and the vast forms of the arapaima ‘head and tailing’ all around, I conjured yet another new plan that would unlock the conundrum of how to catch these monstrous fish.

I tried everything: my great friends Tomasz and Tomek at the brilliant Polish operation Pike Terror Flies had tied me some huge and beautifully lithe fly patterns of up to 10″ long – great, articulated monsters that swam with a seductive action that perfectly mimicked the small armoured catfish that arapaima are reputed to eat. Big fly, big fish, right? However, with so many relatively small baitfish on offer, the vast fish seemed immune to the charms of these beautifully tied flies. I tried monstrous buoyant-headed flies that hovered just above the bottom in the style of the reservoir trout anglers’ booby pattern, that could be fished ultra slow. I tried big surface flies imitating a wounded baitfish, and smaller, flashy, gummy minnow patterns that mimicked the million-strong swarms of baitfish. After a couple of hours at the vice early one morning, I even created a pattern that mimicked half a dozen of these sparkling little fish on hookless droppers, reminiscent of the infamous spinfishers’ Alabama rig, convinced that the arapaima swallow these small creatures in big mouthfuls rather than individually.

I experimented with a variety of ultra-heavy sinking lines, right up to a 750-grain beast designed for sailfish fishing, basing my approach on the theory that it would cut through the water column quickly and allow more fishing time, but actually, retrieving this line ultra slowly meant hooking the bottom in all but the deepest spots.

Finally, using one of the big, 10″ flies my Polish friends had sent me, I had a take – a strange, electrical ‘pop’, followed by a distinct but subtle heaviness in the line. I set hard, with a classic, tarpon-style strip-set, and for a moment I felt the weight of a big, big fish, before the fly came away and I was left exasperated and fishless.

Rafael told me that he would show me an arapaima’s skull when we returned to the lodge, and seeing the fish’s bony maw, I realised that conjuring a take was only part of the conundrum of catching one of these huge fish.

Ultimately, after Lance had managed to show the way with two handsome juvenile fish, I did as I was told and adopted Allan’s fly. Predictably, I finally managed to catch an arapaima. At 50lbs, it was a baby, but it was an arapaima nonetheless, and the realisation of a boyhood dream. Seeing this remarkable creature up close was unforgettable. As I cradled it gently in the margins prior to release, the pirarucu stared back at me with its strange, beautiful little violet-hued eyes. Its whole form was utterly unlike anything I have ever seen before: a bony, armour-plated head, resolving from olive green into a rich gold, and transforming into a vast, sleek blade of a body, with the tail darkening to a sooty black, decorated with remarkable, saucer-sized scarlet-tipped scales.

The following morning, Lance upped the ante with our first ‘proper one’ – a fish of way over a hundred pounds. What a captivating sight it was. Doing my best to deal with the green-eyed monster of jealousy, I photographed my friend with his trophy. I congratulated Lance through gritted teeth, and clapped him on the back with just a little more force than was perhaps necessary. I may have called him a “jammy bastard” at some point. We clambered back into the skiff, and I picked up my 12wt with a new resolve.

Then, finally, it happened.

Arapaima often betray their whereabouts by sending bubbles to the surface. These aren’t the beady little tench bubbles that British coarse anglers know. These are huge, football-sized globes of air that wobble up to the surface. You simply cannot miss them.

It had been a tough morning, but suddenly I saw a number of these huge bubbles off to my left, and I was instantly galvanised.

I cast the huge fly towards the target, and impatiently counted it down into the depths. After 30 interminable seconds, I started the excruciatingly slow retrieve, and after a few seconds, my patience was rewarded as the line took on that same heaviness that I had experienced before. I jagged the rod back sharply and suddenly felt a remarkable violence thrashing down deep in the dark, tannin-stained waters.

In a split second, the entire skiff was twisted around fully 90 degrees with the savage, wild quality of a fairground ride. We were wrenched round not by the prow, but by the vast weight of the stern and the engine. The line scorched through my fingers, and I felt the monstrous power of the huge creature as it shook its head with a truly astonishing ferocity.

I have rarely known such a huge adrenaline rush, and I felt a pure, unalloyed relief as the running line shot up through the rings and I had the fish safely on the reel. I leant hard on the fish and for a few precious moments, I felt its impossible, primal strength. I have caught some big fish over the years, including big sailfish, and tarpon to 160lbs. This was bigger. Much bigger. The line shot up through the water column and I braced myself for my first sight of it.

Not a 50lb tiddler. A monster. A true gigas.

And then, in a heart-breaking moment, the hook-hold gave way, and the mighty creature was gone.

I felt sick.

It was a bitter, bitter pill to swallow after all of those long hours and days of patient fishing, tossing those massive streamers across the wide waters of the lagoons and retrieving the fly at the agonisingly slow pace these vast hulks seem to prefer.

My friend Rafael, one of the very best guides that I have ever fished with and one of the most experienced arapaima guides in the world, looked stunned. “I’ve never had that happen before,” he said. After a long silence, he added, perhaps a little unnecessarily, “That was a big one!”

Rafael was positive: he consoled me by telling me that I had done everything right, hitting the fish hard with repeated strip-sets in the style of the tarpon fisherman, and retaining heavy pressure on the fish. He urged me to check the 8/0 hook and the 130lb leader and to get that fly back in the water.

But I knew…

The real brutes – fish of two metres and up – are a rare catch indeed. They’re there alright – Rafael showed me a picture of a fish caught earlier in the season that was way, way over two metres long and simply mind-bogglingly huge – but you don’t get many chances with fish this size. When you do, you really have to make them count. My chance might not come again.

So it proved.

My friends Lance, Jonny and Breno all conjured fish that were well over 100lbs, with Breno’s best fish taking the honours at 190cm. Lance managed two magnificent fish of 155 and 165cm, while Jonny left it until the last half hour to pull out a beast of 170cm. Each of these fish was utterly magnificent, and left my 50lb tiddler well and truly in the shade.

And yet the real monsters – fish of two, three and even possibly four metres in length eluded us all.

This time, at least.

As the last rays of the sun guttered and died on the glassy waters of the great Amazon river far below, I pushed the recline button down and took another last, wistful look at that livid, line-burnt scar seared into my thumb. I knew that I would simply have to come back.

Perhaps next time I’ll have the humility – and the brains – to do as I’m told. And perhaps next time I’ll finally put my hands on a real gigas.

Want to go?

Pirarucu is the brainchild of brilliant jungle anglers Rodrigo Salles and Marcelo Perez at Untamed Angling (www.untamedangling.com). It is more than just a fishing trip – it is a journey into the very heart of the Amazon rainforest. Everything – from the exquisite music of the birds at dawn to the delicious catfish suppers and the icy Caipirinha on the dock – is a true immersion into the culture of the Amazon jungle. It is a unique and very special experience. And despite the remote location, the whole operation, including the brilliant guides, is remarkably professional.

Email at mattharris@mattharris.com

For big predators like arapaima, Pike Terror Flies are very hard to beat: www.facebook.com/piketerror

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.