The 1939 shooting season

How the outbreak of World War Two impacted gamebirds, shoots and keepers.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of World War Two on 3 September 1939. Gamekeeping and shooting, like all other rural activities, were affected by the conflict which was to last until 1945. Large swathes of the countryside were requisitioned by the government for military use; woods, hedges and old pasture land were grubbed up for cereal and vegetable production, with a resultant loss of habitat for game and wildlife, and poaching increased dramatically due to food shortages and rationing.

Several days before the declaration of war, many married gamekeepers living in remote areas received a batch of evacuee children either from London or the nearest large city. Notwithstanding the challenge of coping with boys and girls from an urban environment who often found the countryside a scary place having never seen farm animals, gamebirds, rabbits, deer and other creatures, they invariably looked after their charges well, providing them with nutritious meals and teaching them how to skin and paunch a rabbit, grow vegetables, look after chickens and pigs and numerous other countryside skills. Indeed, quite a number of former evacuees kept in close touch with their keeper host after returning home.

Some gamekeepers were obliged to find billets for middle-class land girls rather than evacuees, but generally found them more of a trial than children as they expected to flush toilets, have baths and other urban amenities rather than fetch water from a well, use an earth closet at the bottom of the garden and eat rabbit stew or pigeon pie for dinner. Others took in senior army officers who chose to live off base, civilians who were employed at military establishments or foresters who had been transferred from other areas for essential purposes.

Gamekeepers serving in the Territorial Army joined their units immediately after war was declared. Other keepers of military age were called up to fight in the Army, the Royal Navy or the Royal Air Force and sent to training camps. Men who were considered too old for the armed services remained in post but were usually instructed by their employer to combine gamekeeping duties with forestry, farm work or general estate work.

Surprisingly, a large number of young gamekeepers who enlisted in the armed services received an ‘Indefinite Postponement’ letter shortly after they had begun training, were sent back home and were given a ‘reserved occupation’ status as their ability to control vermin, to assist with food production or forestry operations and their intimate knowledge of the countryside was considered to be of more importance than their fighting capabilities on the battlefield. Some, though, were recruited into top-secret, elite Civil Defence units where they were trained in advanced communications and guerrilla warfare in order to defend the country in the event of an enemy invasion.

Members of the gamekeeping profession exempted from military service joined a variety of home defence-related organisations following the outbreak of the war. Gamekeepers, especially those with a larger physique, put their intimate local knowledge to good use by serving as constables with the Special Constabulary assisting regularpolice officers with their duties. Some became A.R.P. Wardens or acted as part-time fire watchers, usually where their employer’s country house had been taken over for military use or converted into a hospital or a school. Arthur Hill (pictured right), Headkeeper at Gaddesden Park in Hertfordshire, even managed to fit in his normal duties with those of pest control officer at Brocks Fireworks factory at Hemel Hempstead, which was temporarily being used to produce military explosives.

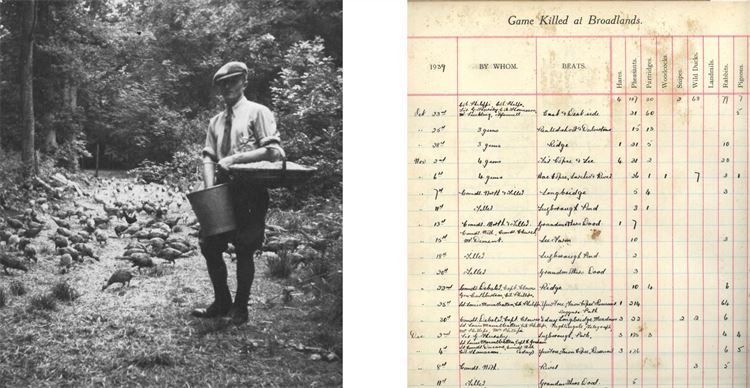

Shooting began as normal in August 1939 and continued until after Christmas, with retired keepers and beaters helping out on shoot days in place of men who had gone to war or had been directed to work on the land. Sportsmen – civilian and uniformed alike – took full advantage of the game available that autumn, knowing that things were likely to change. On the Elveden estate in Suffolk alone, 21,170 pheasants, 799 partridges and 2,099 hares were shot. At Broadlands in Hampshire, a much smaller establishment, the Guns brought down a bag of 1,135 pheasants, 128 partridges, 48 hares and 7,145 rabbits. Further north, on Wemmergill Moor in Co. Durham, 511 red grouse were killed which represented an unusually low bag for the property as 1939 was generally a good year for grouse. While at Eishken in the Outer Hebrides a total of 104 stags, 57 hinds and 257 red grouse were taken with 7 salmon and 1,081 sea trout landed.

On a personal level Major Raymond Lees, a veteran of World War One, records in his gamebook: “War declared Sept. 3rd: I rejoined Regimental Depot on 6th.” The Major nevertheless goes on to mention that during periods of leave he managed to attend nine walked-up or driven shoots between 9 September and 26 December, killing a total of 4 pheasants, 60 partridges, 5 pigeons, 1 hare and 14 rabbits. His best day, 30 September at Leeds Castle in Kent, yielded a bag of 39 partridges and 3 rabbits.

Shortly before the end of the 1939 shooting season, landowners were ordered to cull large numbers of pheasants and partridges on low-ground shoots and send them to towns and cities to alleviate food shortages. Game farms were also instructed to do the same, and the staff at the Wiltshire and Hampshire Game Farm near Andover accounted for around 1,000 pheasants per day for despatch to the London markets for several weeks running.

Gamebird rearing was subsequently banned throughout the country for the duration of the war. Indeed, anyone caught illegally feeding pheasants, partridges, duck or park deer with grain or other food stuffs was liable to receive a hefty fine or even imprisonment. Shotgun cartridges were rationed with priority being given to pest controllers rather than sportsmen, but many landowners and gamekeepers were relatively unaffected having large numbers stocked in gun rooms and keepers’ outhouses so could go out into the field with dog and gun in pursuit of a few birds for the table as and when required.

Notwithstanding all of these restrictions, shooting was able to continue during the war years on a small scale on some low-ground shoots owing to residual stocks of pheasants and partridges in woods and hedgerows. Some gamekeepers even surreptitiously preserved birds through nest management in order that landowners and their guests could enjoy a little sport when home on leave from the armed services.

Grouse shoots were relatively unaffected by the war, but moors suffered due to minimal gamekeeping which resulted in an increase in avian vermin and poaching both by local people and locally based servicemen keen to augment their meat rations. Some moors were requisitioned for military training purposes so were out of bounds to shooters and members of the public alike. Others, such as Ruabon moor in North Wales which was lit up nightly as a decoy to divert German bombers carrying out incendiary bombing raids on Liverpool away from the city, experienced severe habitat loss due to being regularly set alight by bomb explosions or practice shellfire and became unsuitable for shooting.

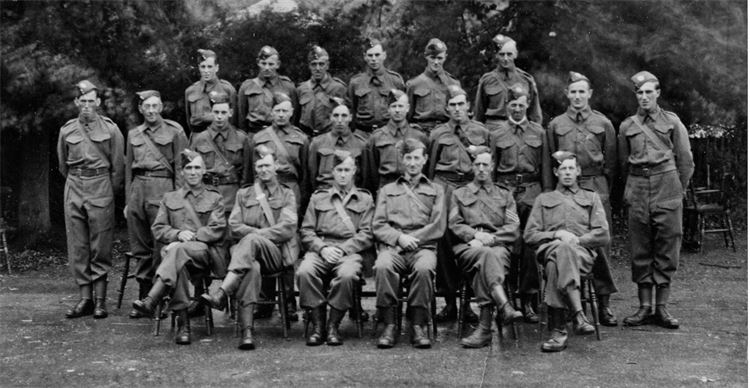

Gamekeepers aged between 17 and 65 not already involved with home defence duties were recruited into the newly formed Home Guard in May 1940. Some were veterans of World War One and put their superior gunnery and fieldcraft skills to good use as instructors or as unit armourers. Many initially supplied their own guns or rifles and ammunition due to weaponry shortages. Indeed, the Broadlands Estate unit of the Home Guard in Hampshire (pictured above) was armed with sporting guns and other weapons from Lord Mountbatten’s gun room as an interim measure until the War Office was able to supply them with Army rifles!

Thereafter, gamekeepers continued to combine Home Defence duties with pest control, farming, forestry and other work until the cessation of hostilities in 1945. They also contributed to the war effort by trapping or shooting large numbers of rabbits and pigeons, which were either sold directly to local people to supplement their meat rations or sent to a market in the nearest town. Pigeons were highly sought after at this time and realised between 4d. and 3/6d (up to £6.89 in today’s money!) per bird depending upon supply levels.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.