Side-by-side or over-under shotgun

Top game shooting instructor Simon Ward shares some tips on how to make the most of both shotgun configurations.

Although I have now shot with a Perazzi over-under for more than 15 years, I shot both clays and game for 10 years with a Holland & Holland Royal side-by-side. There is no doubt that both configurations deserve their place in the game shooting field, but there is no getting away from the fact that they are fundamentally different in design. Therefore, in order to get the most out of them respectively, one’s technique must be adjusted accordingly.

If we compare a typical 28″ side-by-side with double triggers and a straight-hand grip, with a 30″ over-under with a single trigger and semi-pistol grip, there are a number of key differences in their design which will have a bearing on one’s performance in the game shooting field.

Weight matters

For starters, the over-under, which will typically weigh in the region of 7lb, would be a whole pound heavier than the side-by-side. So, using identical 28g No. 7 loads, for example, the felt recoil in the side-by-side would be noticeably greater, as would the muzzle-flip. Not only will the additional weight in the over-under absorb more of the recoil, but, due to the configuration of the side-by-side’s barrels, the recoil comes back in a dogleg fashion – backwards and slightly to the side, following the line of the stock which, typically, would have more cast in it than in the over-under. Therefore, you will feel the recoil differently depending, of course, on which trigger you pull. With the over-under, however, the recoil will come back, more or less, in a straight line.

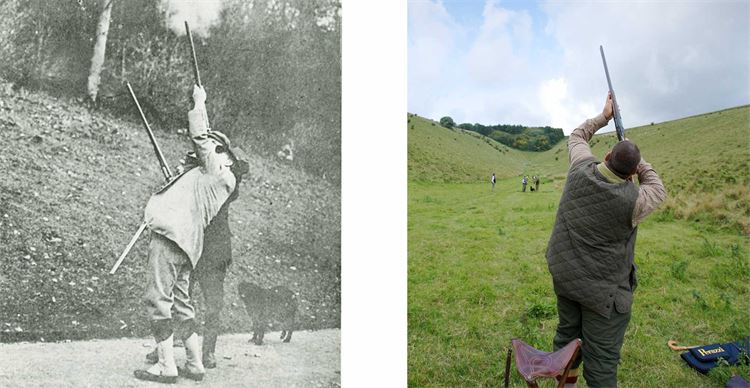

To reduce the felt recoil and muzzle-flip in a side-by-side, as well as improve its pointability, I recommend shooting with a much straighter lead-arm than you would with an over-under (see images overleaf). Indeed, if you held the fore-end of the side-by-side with your lead-hand, the gun would invariably feel short, and as a result you would have less control of the gun. So, not only does the straight arm absorb recoil (rather than your shoulder), but it also gives you greater control of the barrels and therefore improves your accuracy and precision.

In a similar way, the Prince of Wales, semi-pistol and full pistol grips, typically found on over-unders, in effect keep the grip-hand locked in place at the start of the mount, during the mount and when you take the shot, giving you greater consistency. Your arms also take out a lot of recoil and these grips help to absorb felt recoil.

If you watch some of the great side-by-side Shots of today in action – the likes of the Duke of Northumberland, Lord James Percy and Phil Burtt – they all shoot with a very straight lead arm. And if you browse through Jonathan Ruffer’s

And, because of the increased manoeuvrability of the lighter and generally shorter traditional side-by-side, a spot-shooting technique tends to be the most effective method, particularly for crossers. This is where one connects the muzzles to the bird before the mount is completed – i.e. you move the unmounted gun with the bird and then mount onto a spot in front of the it and pull the trigger whilst keeping the gun moving. So, essentially, you point the shot where you want to shoot, rather than using the weight of the gun – as you would with an over-under – to generate swing and momentum. As a result, the movement of the gun tends to be a lot more economical.

With an over-under, however, the standard method is to swing through the bird from behind, pull away and take the shot whilst keeping the gun moving This is because with the longer barrels, which also tend to be more muzzle-heavy than the side-by-side’s, and additional weight, you can generate momentum more easily.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SIGHTING PLANES

Another of the key differences between the over-under and the side-by-side is the sighting-plane (i.e. what you see when you mount the gun and look down the rib). With a side-by-side, when you look down the centre rib you can see both the left and right barrels. Therefore, your lead eye must be directly over the centre of the rib if you want to shoot with any level of consistency. If it isn’t, your shot will not go where you are looking. There is no denying that, with its narrower, single sighting-plane, the over-under has better pointability.

In order to achieve an accurate gunmount with a side-by-side, you tend to need more cast in the stock. It is also easier to tell if your eye isn’t directly over the centre of the rib on an over-under, because, when you mount the gun, you will invariably notice that you can see more of either the right side of the barrels (too much cast on a right-handed gun) or left side of the barrels (not enough cast).

Moreover, with the side-by-side’s broader sighting-plane, if the gun is in your shoulder for too long, your eye may be drawn away from the bird and to the barrels. The over-under has an obvious advantage in this regard, too, as there is less visual distraction and therefore you can mount it earlier, thus employing a deliberate (rather than instinctive) method more easily.

The greater visual obstruction of the side-by-side’s barrels is particularly relevant with very high or long-range birds as you are more likely to lose sight of the bird behind the barrels during the swing. Side-by-sides also shoot lower to point of aim than over-unders, irrespective of comb height. So, with longer-range birds, where the visual profile of the bird shrinks in size, the narrower, single-sighting plane of the over-under makes the task of holding the line of the bird a lot easier. Essentially, you have greater pointability and a greater degree of precision.

With low to medium, straight-driven birds (up to 25 yards) with a side-by-side, the technique is to swing through and pull the trigger when you lose sight of the bird, keeping the gun moving. However, with high, straight-driven birds with a side-by-side, because of the visual obstruction of the barrels, you are better off treating the bird as a crosser by moving your feet, dropping the opposite shoulder and canting the barrels so that they are parallel to the line of the bird. That way you won’t have to lose sight of the bird (essentially turning it into a crosser). The likes of Lord James Percy, the Duke of Northumberland and Phil Burtt turn almost all high driven birds into high crossers as it is obviously easier to hold the line of the bird if you can see it.

But in terms of traditional low-ground partridges and pheasants, or driven grouse, a traditional side-by-side is still a wonderful and effective tool for the job. The wider barrel profile can actually be an advantage on a grouse moor or with low partridges over hedgerows as it is easier to pick up and gauge the true line of the bird.

At the end of the day, as long as your gun fits you, it’s not so much what you use, but how you use it that really matters.

The benefits of both:

Side-by-side

• Aesthetically more elegant

• Manoeuvrability in a tight corner

• double triggers give instant barrel selection

• Easier/faster to load with wider gape

Over-under

• Better pointability

• Less felt recoil

• Single sighting-plane

• wider range of loads on the market

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.