John Trickett

Over the years, artist John Trickett has created hundreds of paintings which beautifully capture the allure of our sports. And yet, amazingly, he has never pointed a gun at bird or beast nor wetted a line in hope of a fish.

Since the first issue of Fieldsports hit the shelves in 2006, we have interviewed countless ‘sporting’ artists who are as passionate about spending time out in the field – be that with a gun, rod, rifle, dog or falcon – as they are about spending time at the easel or workbench.

Time and again we have pointed towards their passion, their immersion in this way of life, and highlighted it as being key to their success as artists and being able to accurately portray the landscapes, quarry and special moments that make our sports what they are.

John Trickett is different. Yes, his work is absorbingly atmospheric, capturing the sort of details that nostalgic sportsmen like to ponder over at the end of the day by a roaring fire, dram in hand, and yet he has never pointed a gun at bird or beast, nor wetted a line in hope of a fish. Here’s an example of a ‘non-sporting’ artist who has enjoyed much success in the world of sporting art.

John has, however, worked hard to learn about fieldsports – game shooting in particular – to ensure his art is as accurate as possible. “Over the years, I have been on many shoot days to glean a better understanding of how they work, and get a feel for the atmosphere of the day,” he explains.

“I love all wildlife from deer to gamebirds and, although I could never pull the trigger myself, I totally get why people shoot. I know that without the people who shoot and the work that keepers do, there wouldn’t be the abundance of wildlife we now see in many parts of the country. I particularly love going to my nearest grouse moor and seeing the variety of birds that benefit from its management.”

In fact, John’s only lifelong sporting passion is football. At the age of 18 he relocated from his hometown of Grimsby to Torquay where he signed a professional contract. “I lived above a nightclub back then and in my free time when I wasn’t training or playing football, I would paint and draw,” he explains. “One day the club owner came to my apartment and was amazed by the work I had produced and really encouraged me to push it further.” So he did, and subsequently began selling his art – mostly posters of icons such as Che Guevara and Jimi Hendrix – as and when he could.

Around Christmastime a couple of years later, John’s mother fell ill. He travelled back to Grimsby to see her. “She was in a far more serious condition than what I had been led to believe, and it turned out that she only had a matter of days to live,” he explains. “I decided right there and then that I would stay up north and live with my dad, leaving all of my art and belongings in Torquay.”

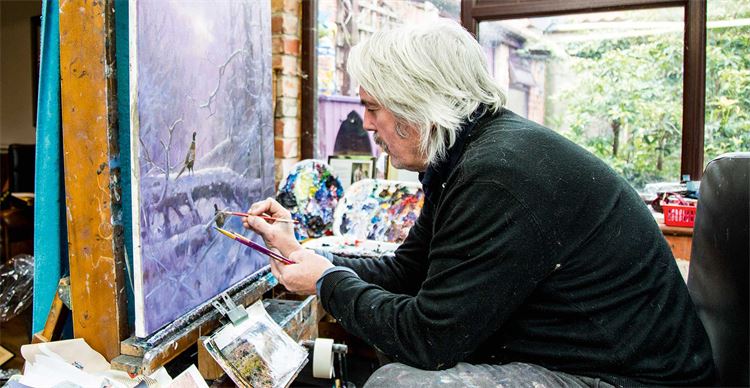

Little did John know at this difficult time in his life, that the move would shape his working career dramatically. “After a few years of working as a forklift driver to pay the bills, I decided to host a solo art exhibition in the local library that had an excellent display room,” he says. “In my spare time, mostly during evenings after work, I created 40 oil on canvas paintings to sell that were relevant to the famous fishing port. Boats, marine life, wild animals, shire horses – that sort of thing.”

Astoundingly, every single painting sold – the most notable being a large-format painting of a shire horse that fetched £130. “It was the first time any of my pieces had broken into treble figures!” he remarks. “And the exhibition gave me the confidence to have a crack at painting full-time.”

John continued to develop a style of art that would prove very popular. And, not long after taking the plunge and quitting the day job, he met art dealer Sally Mitchell – the lady largely responsible for shaping the remarkable portfolio of paintings that are proudly hung on the walls of sporting lodges and homes across the country.

“At the time, Sally was making a name for herself selling exquisite antique paintings,” he says. “We made contact and I travelled on the train with a few sample paintings. Believe it or not she bought them on the spot, and asked me to start working on some springer spaniel paintings. Which I duly did.”

And so began John’s journey into sporting and countryside-themed art. The train journeys to Sally’s gallery bearing new paintings increased in regularity. “I spent a lot of time on trains,” laughs John, “but I met my wife Jackie on one journey, so it had its perks.” Eventually, and perhaps inevitably, a working contract was drawn up — Sally signing John as her first contemporary artist. The success of the partnership saw other leading sporting and equestrian artists join the fray, including Malcolm Coward, the late Mick Cawston, Paul Doyle and Fred Haycock.

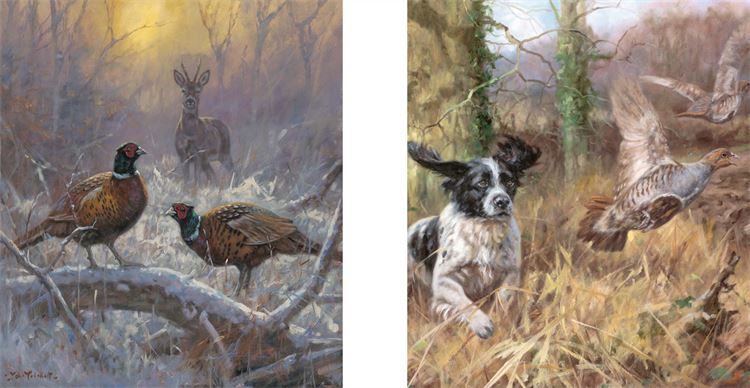

In the 40 years that have passed since, John has created hundreds of paintings which epitomise the beauty and allure of our sports – from gundogs flushing pheasants, and shooting parties crunching across frost-covered ground, to hares, deer and gamebirds in their natural habitats. “You can thank Sally for all of that,” he admits.

“I would never have considered going to the depths that I have to create my paintings. She organised my visits to various shoots and estates. I’m invariably treated very kindly by shooting folk, and I’ve enjoyed being a part of many days, despite not actually participating in the shooting itself.”

THE PROCESS

“I sketch what I want to paint on every canvas before I reach for the paint,” says John. “I will draw the position of the birds and then any surrounding features. Then I will look at images online and the hundreds of photos I have taken, to refer to detail for a particular species.”

The next stage is developing shapes and adding the various colours and textures. He calls these the ‘loose’ elements, which are suggestive and draw one into the art whilst gently stoking the imagination.

John then focuses on the shadows and movement. “I will refer to images at this stage, but only for specific detail and inspiration for possible light effects. Photographs do not always represent true motion, which is why drawing from a photograph pixel for pixel does not work for me,” he admits.

Once he is happy with the overall image composition and colour, John will let a painting dry and come back to it to add the finishing touches – that final 10 per cent. “This is the most vital stage to get right,” he acknowledges. “I will add the main detail to the beaks or feathers, add the edges of light and whites to the eye, and enhance the crispness of various elements.

“It is all about the balance of what is detailed and what is suggestive,” he says.“If I painted everything accurately, my work would lose its atmospheric qualities.

“The best painters I have ever seen, do this effortlessly and so cleverly. They will paint a horse or an animal, focusing on the intricacies unique to the subject, but then allow intuition and experience to flow over the non-important parts.”

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.