★ Win a Schöffel Country shooting coat for everyone in your syndicate worth up to £6,000! Enter here ★

Politics by other means

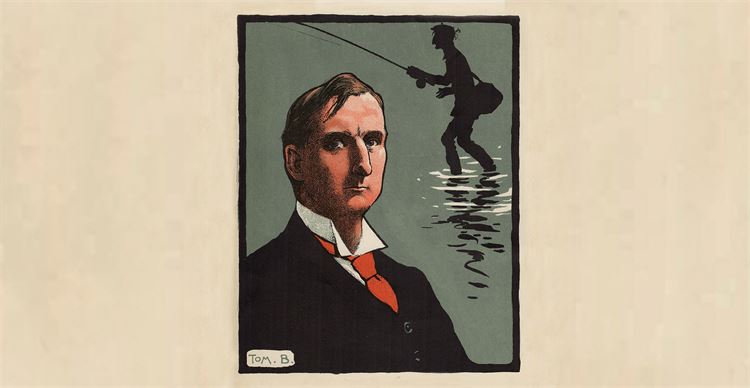

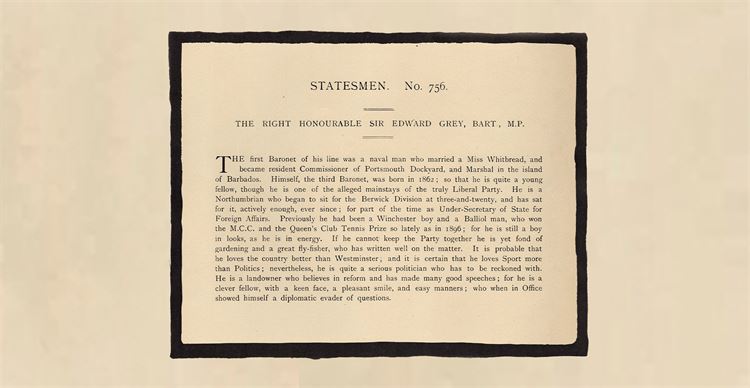

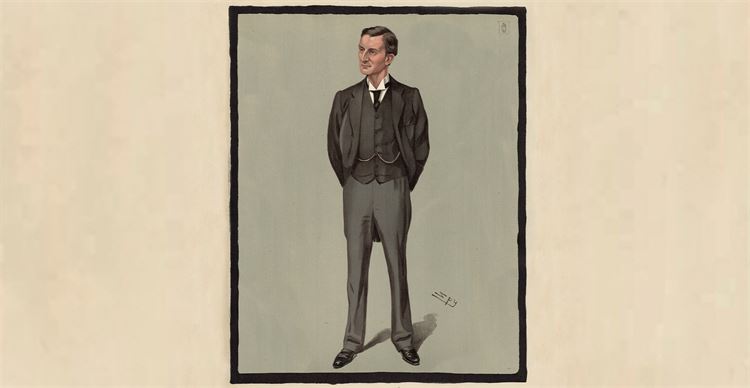

Sir Edward Grey, Foreign Secretary, who went fishing at a time of national crisis. By Jeremy Paxman.

On the first day of the Battle of the Somme, over 19,000 British soldiers were killed. On the same day, the Foreign Secretary went fishing and caught six trout, the biggest of which was 1lb 9oz.

Put as baldly as that, Sir Edward Grey, the offending statesman, sounds a callous bastard.

A tall, thin, Northumbrian toff with dark hair, blue eyes, thin lips and a long nose, Grey was a quiet man. I only know he was fishing on 1 July 1916 because the other day his great-great-nephew (he had no children of his own) loaned me his fishing diaries. Like so many of us, Grey kept a record of his fishing and shooting exploits for decades, as enthusiastic when he was a statesman on the world stage as he had been as a schoolboy at Winchester. The thrill never dies.

He even kept running totals – so that we know in 1913 he caught 152 trout with a total weight of 205lb, and in 1914, 179 trout with a total weight of 230lb.

To some people, Grey’s fishing diaries and gamebooks are probably as dull as a train-spotter’s lists of locomotives. What possible significance can there be in knowing that on 11 June 1880 he caught a 1lb 10oz trout at Alresford on a Grey Gnat? A trout swimming in a stream is wondrous – stippled and mysterious. But reduced to an entry in a fishing journal it is an act of accountancy. It’s like trying to explain the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel by calculating the amount of paint used.

It’s pointless to deny that there is something obsessive about the black ink-and-pen records. We’re all a bit like that. ‘How big was it?’ I asked a friend in Sutherland last month when he told me he had caught a salmon. In truth, size of fly matters, while the size of the salmon is just chance.

The important things of last month were the cries of the oyster-catchers, the sight of the wagtails and chaffinches at the water’s edge and the thrill of seeing an osprey, a hen harrier and a sea-eagle. They rather put the Prime Minister, Leader of the Opposition, Donald Trump, that absurd man in the boiler suit in North Korea and other assorted pipsqueaks of politics in their place. I should have seen none of the birds if I hadn’t been fishing. Of course, Edward Grey thought fly fishing more important than being listened to in the Chancelleries of Europe.

Nonetheless, Grey was the longest-serving Foreign Secretary of the 20th century and the originator of one of the most resonant expressions of the modern age, when he remarked at dusk on 3 August 1914 that “the lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.”

There is a now tediously well-established way of rising up the greasy pole, involving striking an attitude at university and never growing up, then working one’s way to Westminster through bag-carrying as a ‘special advisor’ and running for election in an unwinnable seat, before being given a chance to join the army of elected drones. It is always an urban life. The problem with urban lives is that they shorten your horizons. They do the same thing to your imagination.

Edward Grey was cut from a different cloth altogether, virtually ineligible for the life of a modern careerist. He belonged to a class now non-existent in British life – privileged men who believed that political life was some sort of calling. He seems to have been a lazy young man, playing football and tennis, ending up with a Third from Oxford, and then casting around for something unpaid to do. He ended up as an MP, because that was what certain people did: Grey really did look the sort of toff who had just walked out of a `Spy’ cartoon. But when, in the summer of 1895, he lost his junior position in the Foreign Office he said that he and his wife “are both very glad and relieved”.

He was not, however, relieved enough to turn down the post of Foreign Secretary when the Liberals returned to power in 1905. Now he had to content himself with scurrying off to the chalk streams whenever the chance arose. His cottage on the Itchen became, he said, ‘a sanctuary’ and the river ‘a sacred place’.

As a countryman, a fly fisherman and a bird-lover he was, inevitably, sneered at by the metropolitan elite for his enthusiasms. William Ewart Gladstone, the four-time Liberal Prime Minister, is said to have remarked at one point that there was really nothing to stop Grey becoming Prime Minister. When it was pointed out that Grey preferred fly fishing to politics, it is claimed that the Grand Old Man used the word ‘contemptible’. Pots and kettles, I think.

But the fishing diaries, with their records of where and when, weather conditions, and which flies were effective, are another matter. The true angler recalls if not every fish, then certainly a decent number of them. The fewer they are, the more you remember them. Dullards are excited by their weights, poets by their markings.

He had been lucky enough to be sent away to school at Winchester in September 1872. ‘Etonians’, they say, ‘think they rule the world. Wykehamists know they do.’ Grey was cured of the school’s usual superciliousness by being able to fish for trout on the schools’ four miles of the River Itchen. Having teenage access to one of the world’s premier chalk streams is a privilege given to few, but Grey repaid it with a lifelong devotion to the natural world.

The greatest need in fishing is the requirement to be quiet and unobtrusive. It is the polar opposite of the noisy ‘look at me!’ strutting of most political leaders and has the joyous compensation of allowing you to watch the world turn around you.

As Britain slid into the Great War, in August 1914, the distraught French ambassador in London (‘aged, drawn and flushed’, according to a witness) called to see Grey, to tell him that Paris was declaring war on Germany and to beg for the British military assistance which would end up costing so many hundreds of thousands of lives. As soon as the meeting finished, Grey took the Foreign Office car. His destination was his familiar London retreat: the birdhouse at London Zoo.

The political establishment – as pernicious then as it is now – sneered at him for seeking solace in the natural world. But what do they know?

And was there anything wrong with Grey going trout fishing on the first day of the battle of the Somme? In the modern age, some creepy spin doctor would rule it out on the grounds that it would look bad in the Daily Mail. But in 1916, it took several days for the extent of Commander-in-Chief Douglas Haig’s catastrophe to become clear. And anyway, nothing would have changed had the Foreign Secretary stayed in London instead of heading down to Hampshire: by 1916, politics and politicians had been shoved aside by men in khaki with well-upholstered shoulders and much gold braid. Grey ventured abroad only once during his 11 years at the Foreign Office. Personally, I do not find him an attractive politician.

By contrast, his devotion to the Hampshire countryside was intense. If politics kept him in London, he walked over Lambeth Bridge to catch the 6am Saturday morning train from Waterloo to Itchen Abbas, where he and his wife slept under the stars blessed by the morning birdsong, wild flowers and the constant babbling of the river.

But his idyll did not protect Grey from misfortune. His wife was thrown from her carriage in February 1906 and never regained consciousness. One brother was mauled to death by a lion, another killed by a buffalo. When his nephew was killed on the Western Front in 1918, a distressed Grey wrote to his sister saying, “what helps me most is watching the stability of nature and the orderly procession of the seasons.” But his own eyesight was failing by then and he was unable to make out the birds he so loved. It eventually got to a point where he was unable to see whether his fly was even in the river or somewhere on the bank.

By astonishing chance, I was invited down to fish on the Itchen the other day. It turned out to be on precisely the stretch of water at Chilland on which Grey used to cast his flies. It is stunningly lovely, with clear water babbling over luxuriant water crowfoot, and though I didn’t hear the Lesser Whitethroat that Grey heard on the same date in 1896 (not that I would recognise it, sadly) it was a moment when all seemed right with the world. The water has not been stocked for generations, so the thrill of taking a 2lb trout on an F-Fly was intense.

Edward Grey’s fishing cottage burned down years ago and all that remains are a few ruins. But ancient photos pinned to walls of the fishing hut show the former Foreign Secretary sitting on a bench with some of his much-loved ducks feeding from his open hand. One of them has even perched on the crown of his deerstalker. He looks like a harmless local eccentric.

In the rather fatuous accountancy of success, Grey’s political life was a failure. He failed to prevent the greatest bloodletting in European history and his political career ended in 1916, aged just 54. He belongs to an earlier time, when events moved slower, when there was time to record your catches in a leather-bound journal over a glass of Scotch. Apart from his one-liner about the outbreak of war, no one thinks about him much these days. But we should be a lot better governed if only we had more people in politics who loved our countryside and understood the vanity of human ambition. FS

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.