- News

- Game shooting

- Fly fishing

- Big game

- Sporting art

- Guest editors

- Gear

- Competitions

- More

-

-

More

-

- No posts selected.

-

-

-

-

★ Win a Schöffel Country shooting coat for everyone in your syndicate worth up to £6,000! Enter here ★

Captain Kenny and the marsh

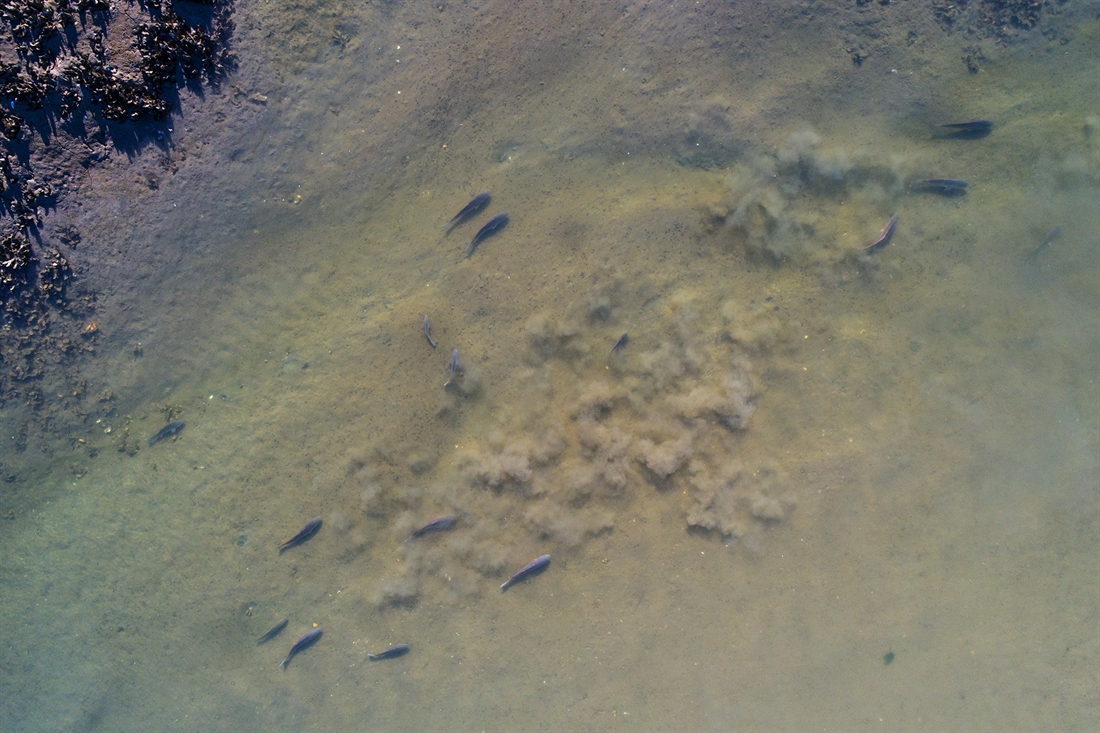

Sight fishing in the shallow and crustacean-rich waters of the Louisiana marsh.

Photographer: Jason Temple

The marsh of Louisiana is a wild place. Put your skiff out of Bayou La Loutre, near the often-flooded cul-de-sac of Hopedale, and you could be excused for thinking you had come to the end of the world. It’s mile after mile of swamp and marsh, a monotonous landscape that holds an eerie and unpleasant beauty. Nothing suggests that humans have ever been here except the deserted crab traps that now house families of oysters, and oil rigs in the far distant Gulf of Mexico puncturing the skyline. It’s the type of wilderness where people get lost forever.

The guys who target redfish with a fly down here have a cultish nature. It’s a pretty new sport, created by the bayou flooding each year and, as it recedes, taking some more land with it. Where grass once grew there are now flats – flats that are full of shrimp and oysters and mullet, and their predator, redfish. These flats have opened up the possibility of sight fishing in shallow water. It’s not unlike targeting bonefish, except you are in the bayou, not in the crystal-clear and white-sanded flats of Belize or the Bahamas. Base camp is probably New Orleans, a city sobbing and coughing with jazz and drowning you in bourbon.

Most natives still catch reds with deadbait. A few of the more enlightened are spinning with cork floats. Those who are fly fishing are downright alien. The taxi driver taking me to the local fly shop in New Orleans wondered why I wanted to go there; “do y’all want proper fishin’ gear, or designer fishin’ gear?” He told me that he had a boat, and when he went fishing he always took two shotguns out with him, “Cause it’s good ta be able ta defend yourself”.

My guide was Captain Kenny, the only New Orleans native to exclusively guide fly fishers. The 10 or so other guides that serve this fishery are all out-of-towners, heading over to the marsh for winter after the tarpon fishing slows down in the Keys. Captain Kenny was what you’d hope any Louisiana native would be. He cussed with a reassuring regularity, his face was etched with years soaked in sun, and his bottom lip bulged with a knot of chewing tobacco. His manners told me he knew the marsh inside out. While each turn looked identical to me, and every view endlessly like the last, this was Captain Kenny’s backyard and he knew it by heart.

We motored through the canals and bayous at a great speed looking for clear water. Louisiana dolphins porpoised, the magical rosate spoonbills flew loftily above us and pelicans, the state’s symbol, dove into the water nearby, hoovering up mullet. The ecosystem of the Louisiana marsh is one of the most fecund anywhere. With each push of Captain Kenny’s pole, a cloud of small mullet scattered before us.

Despite its majesty we quickly realised our day’s fishing would not be a vintage one. The tide had been unusually high, and kept that way by an incoming wind, silting up the water and making it tough to spot fish. From time to time Captain Kenny called out ‘C’mon fish!’ in frustration. When we’d pass over a patch of water with an explosion of stirred up mud – sign of a redfish spooked before we’d seen it – he’d yell, “smoke bomb bastard!” promptly followed by a squirt of spit that only experienced chewers of tobacco can achieve.

In the distance, just off an edge of a small island and amongst a few strands of grass, Kenny’s razor-sharp eyes spot a group of golden tails waving at us. There can be few more exciting views for a flats fisherman: lightly rippling water with fish tails lazily bobbing in and out. It’s a sure sign of feeding fish, their bodies angling down and their heads burrowing into the crustacean-rich mud below, oblivious to the desires of a captivated angler.

We pole gently forward. It’s a practised art, and our skiff moves silently through the water. My line is coiled at my feet: this is not the time to make false casts and strip line off the reel. On a tough day like this there is no margin for error, no second chances. As the boat slows I get a subtle nod from Kenny. With one false cast I shoot 40 feet of line, and my fly, a medley of deer hair and feathers imitating a marsh crab, lands with a plop slightly ahead of the group. Unlike a good shot at the end of a stalk, a good cast while fishing is far from final. I wait a few seconds for the fly to sink into the bayou mud, and then twitch it gently back towards me. The lead fish follows and inhales the fly. I strip-strike and immediately the line is taut. The fish lunks away at a speed belying its size. It’s dorsal fin carves through the shallow water. The oversized head and prehistoric texture give these fish a strange and appropriate beauty in the marsh. It’s what the French call jolie-laide – a good-looking ugly woman – and in this region, where French is still spoken, the fish, with its spooky beauty, seems to fit its birthplace.

At noon we pause. Lunch is a po’boy, 12″-long sandwich that is a New Orleans specialty. Ours is filled with two deep-fried, soft-shell crabs. It’s accompanied by Captain Kenny’s tales of fishing in winter when the water is crystal clear. I ask him about Katrina and he tells me how he stayed put, refused to leave, rode it out. He says it was tough, but that the BP oil spill was ‘media hype’. He has other worries: the bayou is eroding. It’s happening so fast that there will only be one more generation that can fly fish the flats for redfish. The soundtrack to his gloom is the heady breathing of an alligator 20 feet away. A pod of stingrays pass by, working the nearby bank, sucking in shrimp.

I have to concentrate or get lost in the almost-foreign language of Captain Kenny. I also feel lost in this strange environment that seems so full of life and yet is disappearing at a terrifying rate. With the tide still high and the waters still murky, we go back to work, poling and searching for a couple more hours. Then the southern heat defeats us. A lone fish is hardly a triumphant day. “On a good day you can expect more than 20,” the Captain tells me. I don’t really want to hear that, but I don’t have any regrets. In fishing there is deep satisfaction in taking the rare chance when it comes.

Back in the city there was plenty of time to ponder the day. New Orleans feels more European than any other city in America and, at the same time, more authentically American. This is a city that has given birth to blues and jazz, the best food in America, and famous cocktails like the Sazerac or the Ramos Gin Fizz. Down a few of these at sunset, watching giant steam ships roll down the mighty Mississippi, notes from Louis Armstrong floating somewhere in the humid air, and you feel a million miles from the rare and endangered marsh. And yet they both have a haunting wildness and a seductive allure. The urge to return is as strong and addictive as the sassafras leaves – source of the filé powder – that gives character to the New Orleans Creole gumbo.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.