★ Win a Schöffel Country shooting coat for everyone in your syndicate worth up to £6,000! Enter here ★

A day at the lake

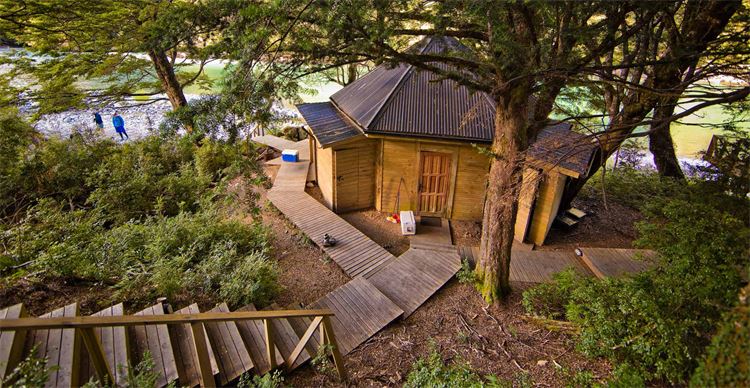

Monster trout in the mountains of Chilean Patagonia.

Some days are special. As Max, Johnny and I tramped over the ridge, we looked down and caught our first glimpse of the lake far below. It was a jewel: reed-fringed and sparkling in the early morning Patagonian sunshine. The last wreaths of mist were clearing, and the tell-tale concentric rings of feeding fish were visible even from way up here.

We quickened our pace as we descended the steep slope, until the treeline obscured our view and we stopped looking for more feeding fish and concentrated instead on weaving through the lengua trees.

We loaded the kit into the boat and dragged it down the tiny, gin-clear feeder stream that weaves through the reeds before entering the lake. Wet-wading in the stream, the icy waters that tumbled down from the Andean foothills all around felt sharp and invigorating.

Suddenly the high wall of reeds on either side of us opened out and gave way to the startlingly beautiful vista of the lake. We clambered up into the boat, and Max rowed us out into the deep water. He set up a drift parallel to the shoreline and had us toss our huge Gypsy King flies as tight to the reeds as possible.

To the purist, the Gypsy King is a monstrosity of a fly – a vulgar mess of foam and rubber legs on an enormous long-shank hook. The wild trout of Chilean Patagonia don’t give a stuff about such absurd prejudices. To them it is a dragonfly, and they eat it with gusto.

Despite the profusion of big, busy dragonflies weaving in and out of the reeds, nothing stirred. The fish had stopped rising. With a good ripple now on the water, and the sun appreciably higher in the sky, I was convinced that the fish would be dazzled and would not want to feed on the surface. Max was confident, however. “Give it time,” he counselled.

My boat partner Johnny Murray is an Irishman. Like many of his compatriots, he can fish a bit. More than a bit.

After 15 minutes, Johnny’s fly was sucked off the top and before he’d even lifted the rod, a big, lusty brown trout went careering through the reeds. Johnny gave it some ‘curry’ and after a lengthy battle, a stunning, scarlet-spotted wild brown trout of over 4lb lay in the folds of Max’s net. It was a big slab of golden treasure, a thick-shouldered brute that had grown fat on the abundant larder of the lake’s cool waters. Magnificent.

Johnny wasn’t done yet. In double quick time, he’d put two, then three, then four plump brown trout in the boat, all between two and four pounds. I hadn’t had a sniff. My congratulations were starting to lack any semblance of enthusiasm. So were my jokes about the luck of the Irish. We were both casting blind and I was fishing just as tight to the reeds. The fish weren’t rising and it was surely just dumb luck whose fly they came to. Wasn’t it?

Finally, my luck changed.

A violent implosion of foam-flecked water where my fly had been and suddenly a big golden shape was framed against the dark green canvas of the reedbeds. The 6wt hooped over and my own trophy rocketed into the high mountain air. Line sizzled off the little reel, and the fish ploughed into the deeps before leaping again. Utterly exhilarating.

Another absolutely stunning fish. Four pounds? At least. Brown trout are all characters, and this fish was no exception. His deep burnished flanks featured large, coal-black spots to complement the red, and he had the mean, malevolent aspect of a killer. He was as baleful and as belligerent as a pike. I studied him for a long moment as he lay still in the water by the boat, gently supported by the mesh of Max’s net.

I reached down and eased out the barbless hook. Rolling the fish gently out of the net I watched him right himself. He hovered almost motionless, and seemed to scowl at me for one last moment. Then, with an angry flourish of his great spade of a tail, he was gone, back into the bottle-green depths.

I’ve caught many trout more than double that fish’s size. I’ve had double-figure wild brown trout in Iceland, New Zealand and even (if you can keep a secret) in the UK. However, I have never seen more beautiful, more perfect trout than the thick-set brutes of the lake, replete with their impossibly deep golden flanks and their exquisite scarlet spots.

I sat back and without asking, Max passed me an icy can of beer from the cooler. The cold beer slaked a thirst I hadn’t even realised I’d acquired, and I took a few long moments to just enjoy the singular beauty of this unspoilt paradise, the light glimmering on the pristine waters of the high alpine lake, and all the worries and cares and deadlines and tax returns of the world a million miles away.

Then a fish rose in front of me. My rod was lying across the boat, out of reach, and with a heavy heart, I did the right thing. I urged Johnny to cover it.

Five fish to one. Time to put the beer down and pull my finger out.

The fishing was slow but steady all through the long afternoon, with a few lithe wild rainbows joining in the fun. Max had promised that the last couple of hours would be the best. He was right. As the sun faded behind the hills, the lake came alive. Now we were not fishing blind but were instead targeting rising fish. Now I’d catch my rival up.

Or so I thought. As the lake resolved into a simple abstract of pink and golden hues, fish exploded through the surface, and a fast, accurate cast was more often rewarded.

Fantastic fishing. A succession of big browns and rainbows lit up the twilight with their spectacular acrobatics. I like to think I’m pretty quick on the draw with rising fish, and I fished well, but Johnny is good. Really good. He has sharp eyes and casts a long and accurate line. By the time the last guttering rays of the sun were dying in the western sky, I knew I had to hand it to my friend. The lake reflected only cold purples and blues as the stars of the southern sky started to twinkle overhead. It was finally time to go. For the record, we caught close to 20 magnificent wild trout to close on 5lb, and fair play to Johnny – he was still four fish ahead. Finally, reluctantly, Max called time. The fish were still bursting through the surface all around as, with heavy hearts, we reeled up and headed for the shore.

After climbing wearily back up the hill, we gazed one last time at the lake, sparkling in the southern starlight. Then we descended the far incline, kicked our waders off and climbed into the truck. Johnny and I drank beer and talked animatedly, reliving a very special day while Max drove us all the way back to the lodge. It was well past midnight when lodge owner Marcel came out to furnish us with delicious pisco sours. Marcel scolded us for our late return, but he is a passionate fisherman and we soon overwhelmed him with our wide-eyed description of the takes and fights and that biggest fish of the day that had of course got away. He grinned at our childish enthusiasm and I knew we were all kindred spirits. Another quick pisco sour and I was asleep before my head hit the pillow.

For the rest of the week, Johnny and I fished the tumbling turquoise waters of the Rio Palena and her tributaries, the stunningly beautiful Rosselot and the Figueroa, tossing huge streamers or big bushy dry flies against the cut banks from a drifting boat, or occasionally thrashing our way upstream on foot, to cast dry flies into every likely looking spot, or to make stealthy bow and arrow casts to sighted fish.

The fishing was as fishing should be: sometimes tough but always stimulating. However there was always a moment on each and every one of those days when my thoughts turned wistfully back to a special, special day. The day at the lake.

Contact

Patagonia Base Camp

Nestled in a remote corner of Chilean Patagonia, Patagonia Base Camp is the brainchild of Dutchman Marcel Sijnesael. Marcel is a passionate fisherman and environmentalist, and he is one of the most disarming and instantly likeable people that I have ever met. His boundless enthusiasm for this beautiful region and its prolific trout fishery is utterly infectious. Marcel’s outlying satellite camps are ranged all through the Palena valley and beyond, and his vision of offering a huge diversity of trout fishing experiences from spring creeks to lakes to big brawling white-water rivers is a reality. Max, head guide Greg, and each and every one of the guides are all great company and the staff at the lodge make you feel part of the family. They all exude a genuine warmth and a quiet professionalism that is the signature characteristic of this unique and very special place.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Fieldsports Journal

Elevate your experience in the field with a subscription to Fieldsports Journal, the premium publication for passionate country sports enthusiasts. This bi-monthly journal delivers unparalleled coverage of game shooting, fishing and big game across the UK and beyond.

Each issue offers a stunning collection of in-depth features, expert opinions and world-class photography, all presented in a timeless yet contemporary design.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.